Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

For C3Places a public space must be inclusive and responsive, allowing people to use it without restrictions and to fulfil socio-spatial needs. To achieve more inclusive and responsive spaces, users should have a voice in the process of planning and design, also known as placemaking (PPS, n. d.).

Engaging people actively calls for appropriate methodologies as inclusive design (Carmona, Heath, Tiesdell, & Oc, 2003) or co-creation, the last is at the core of C3Places research.

C3Places uses the terms inclusive and responsible place to describe a far-reaching framework of principles and best-practice on which communities can build a shared commitment to sustainability in social and urban development. For that, communities should be engaged in the making and transforming of public spaces from the very beginning.

Public space as a shared common good is the fundamental premise – public space is a resource which, if used responsibly, can help transform the way people live, work, recreate, and interact. In placemaking, stakeholders should have a clear understanding on how specific characteristics and shapes affect the experience of the space (Alves, 2005; Stevens, 2007).

Therefore, interested parties as different users’ groups, community facilitators, professionals, local authorities and municipalities, should be engaged directly, their opinions accounted for and their needs responded to by placemaking (Alves, 2005; Carmona et al., 2003; Thompson, 2002; UN-Habitat, 2015).

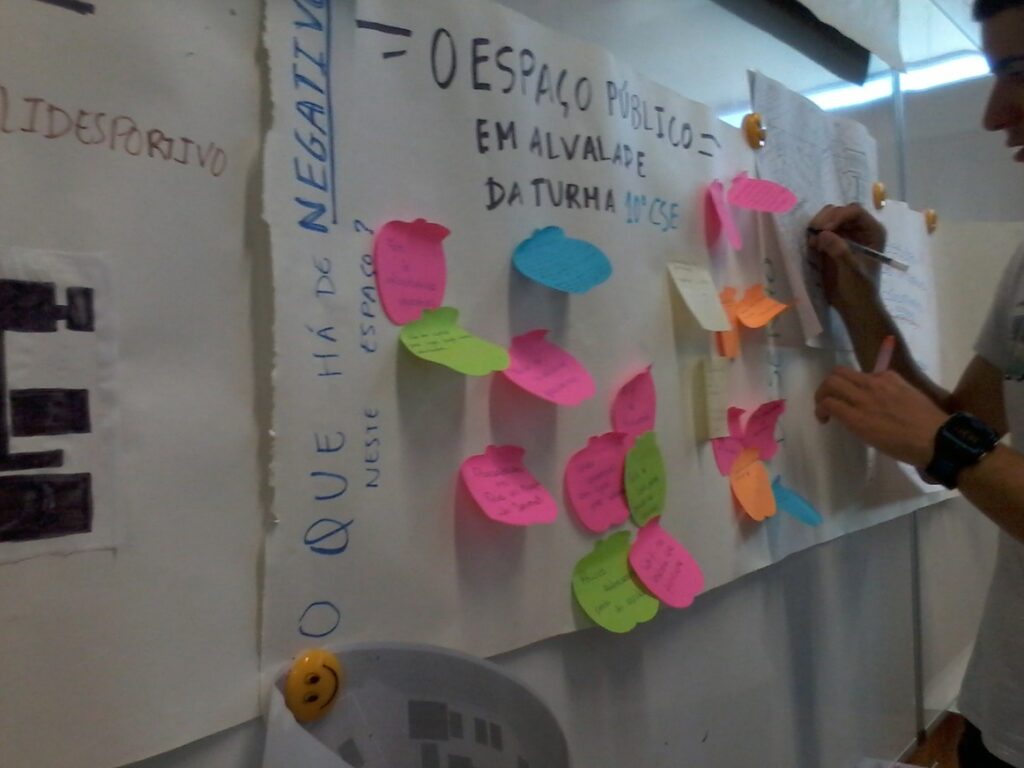

The case-study in Lisbon followed this recommendation and different stakeholders were brought together in the development and operationalisation of Living Labs (Figures 1 and 2) (Smaniotto-Costa, Almeida, Batista & Menezes, 2018).

Figure 1: Living Lab Lisbon – brainstorming exercise with participants to reflect on characteristics of and ideal public space. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2018)

Participative approaches bring challenges of different sorts: in terms of time to be invested, human resources, monitoring and structuring the process that may impose demands that are too high for planners and authorities to see the advantages; in deciding who to involve; the time offset between participation in the process and benefitting from the outcome may be too long for users to engage and, due to transitory needs of users’, too stretched to provide a response while the changes are still valid; questions may be considered too technical or complex for the comprehension of non-professionals and; participation may add a legitimacy to the process but without truly respecting the opinions and ideas of those involved (Alves, 2005; Jupp, 2007; Talen, 2000; Valentine, 2004).

Figure 2: Living Lab Lisbon – group work to draw ideas and proposals for transformation of a public open space. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2019)

However, creating collaborative environments for planning, designing and transforming public spaces is fundamental for a placemaking process more interactive and able to meet the needs of the community, and to produce public places that are more attractive, meaningful, inclusive and sustainable.

Co-creation, as an open process with no previous fixed results, is a challenge for all parts involved but it is at the same time an open door for innovative ideas and solutions. In co-creation a broader range of people come together around the same table to negotiate and reconcile their different needs and interests, solve problems, freely express their concerns and expectations and, ideally, foster a community around public spaces ensuring more sustainable use (Figure 3).

The experiences gained within C3Places in the Living labs in Ghent, Lisbon, Milan and Vilnius are described at the site MyC3Place.

Figure 3: Living Lab Lisbon – outdoor exercise for participants to observe and discover different public open spaces. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2018)

References:

- Alves, F. B. (2005). O Espaço Público Urbano. Qualidade, Avaliação e Participação Pública. Porto: Escola Superior Artística do Porto.

- Carmona, M., Heath, T., Tiesdell, S., & Oc, T. (2003). Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. Michigan: Architectural Press.

- Jupp, E. (2007). Participation, local knowledge and empowerment: Researching public space with young people. Environment and Planning A, 39(12), 2832–2844.

- PPS – Project for public spaces. (2017) The Placemaking Process.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Almeida, I., Batista, J., Menezes, M. (2018). Envolver adolescentes no pensar a cidade: reflexão sobre oficinas temáticas de urbanismo no Bairro de Alvalade, Lisboa. Engaging teenagers in placemaking: Reflections on thematic workshops in urban planning in Lisbon’s Alvalade Neighbourhood. Revista de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território (GOT), 15, 117-142, (in Portuguese).

- Stevens, Q. (2007). The Ludic City. London and New York: Routledge.

- Talen, E. (2000). The Problem with Community in Planning The Problem with Community, 15(2).

- Thompson, C. W. (2002). Urban open space in the 21st century. Landscape and Urban Planning, 60(2), 59–72.

- UN-Habitat. (2015). Adequate Open Public Space in Cities. A Human Settlements Indicator for Monitoring the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda.

- Valentine, G. (2004). Public space and the culture of childhood. Aldershot: Ashgate.