Co-creation – as an active process of engaging different stakeholders, is opening up new opportunities to bring in particular citizens into the design, implementation, monitoring and maintenance of public spaces – to a process that is also understood as the production of public spaces.

Co-creation seeks therefore to make the production of public space, on the one side more effective and efficient, and on the other more inclusive and responsive. By creating opportunities for dialogue and participation and making the production process more trusted it enables the government to deliver better places for the people.

It is more important than ever that citizen engagement and public participation are enacted properly to provide the necessary push and oversight for tailored policies. Co-creation initiatives and social cohesion should be based on the broad and active citizen engagement and community participation.

It is also a multi-stakeholder process that provides guidance and tools for all stakeholders, for government decision-makers and officials, for civil society organizations and activists to translate the outcomes into community-tailored solutions. A vibrant society must rely on initiatives and cooperation of the citizens to be able to attain a better quality of life.

Evaluation of digital tools for co-creation of public open space

Authors: Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Vita Žlender

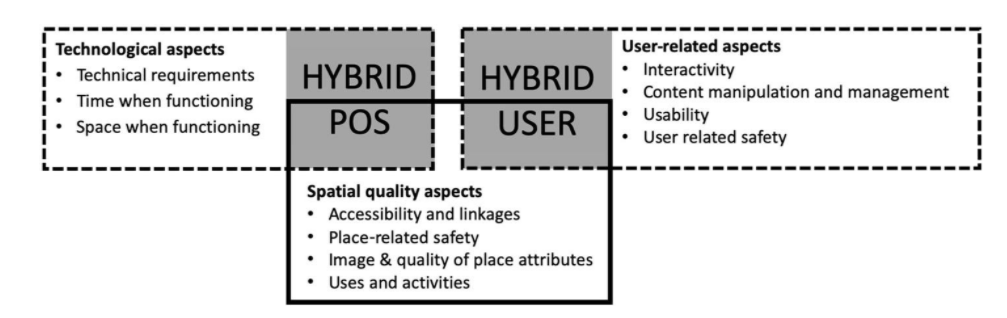

In relation to the Digital Co-Creation Index – a tool to assess, measure and compare digital co-creation initiatives, a conceptual framework was elaborated to convey the penetration of ICT into public spaces. The criteria are structured according to three aspects: spatial quality aspects, user-related aspects, and technological aspects (Figure 1).

SPATIAL QUALITY ASPECTS

The approach to evaluating these aspects is grounded on basic principles of researching, understanding and designing public spaces developed by theorists and practitioners such as W.H. Whyte, J. Gehl, S. Carr and others. Specifically, the criteria, indicators and tools from the Project for Public Spaces “The Place Diagram” (Project for Public Spaces, 2009) and Jan Gehl’s “12 Urban Quality Criteria” (2017) were examined more profoundly.

SPATIAL QUALITY ASPECTS

The approach to evaluating these aspects is grounded on basic principles of researching, understanding and designing public spaces developed by theorists and practitioners such as W.H. Whyte, J. Gehl, S. Carr and others. Specifically, the criteria, indicators and tools from the Project for Public Spaces “The Place Diagram” (Project for Public Spaces, 2009) and Jan Gehl’s “12 Urban Quality Criteria” (2017) were examined more profoundly. In addition, we took into consideration the outcomes of the CyberParks Project and evaluated the performance of the C3Places POS Quality Index (C3Places, 2019) for the Living Labs assessment that we adapted to the current context of POS, with its digital transformation in mind. The main spatial quality aspects which include additional dimensions relevant for ICT penetration into POS, are defined as:

- Accessibility and linkages – Legibility, Navigation, Convenience for movement, Interlinking, Level of physical, social and digital accessibility.

- Place-related safety – Vandalism, Traffic, Injuries, Environmental safety (monitoring).

- Image & Quality of place attributes – Attractiveness, Personalisation and individual creation possibilities, Adaptability, Monitoring, Environmental quality and Ecological sustainability.

- Uses and activities – Communication and education possibilities, Access to information, Sociability, Research possibilities, Playfulness, Variety, Responsiveness, Service provision, Health and wellbeing.

USER-RELATED ASPECTS

To define criteria for these aspects, our guiding question was: Which characteristics of ICT are needed to satisfy use and successful co-creation experiences? As basis for development of criteria the Social Responsiveness Index and the Digital Inclusiveness Index were used, plus a sub-indices of Digital Co-Creation Index (C3Places, 2019) and literature review of existing classifications and criteria of ICT features to enable satisfactory user experience. We considered criteria for methods and approaches selection from “Participedia” (n.d.) and the work of Kaplan & Haenlein (2014), who focused on collaborative projects, such as one on ICT tools, grouping them along two dimensions: type of knowledge that is created within a collaborative project, and mutual independence of individual contributions. We define user related aspects as:

- Interactivity – User’s engagement along with the device/ media/ application used, its type of interaction, degree of interaction and type of experience

- Content manipulation and management – How is it provided and what is user supply?

- Usability – Ease of use, respect for privacy, saving work for future use, customization potential, possibility of choice

- User-related safety – security and privacy assurance technology (protection of personal data, anonymity of ideas, etc.) and social resilience

TECHNOLOGICAL ASPECTS

The guiding question for the technological aspects was: How can digital technology support quality of place and the way the place is used and developed? The main issues to define are:

- Technical requirements regarding software, hardware and network communication, and their installation: is there a need for the internet, are any specific operational systems required, i.e. electricity, speakers, etc.?

- From the time-related point of view: is the ICT tool functioning permanently or temporarily, continuously or intermittently?

- From the point of view of functioning place: is the ICT tool static, located in the POS, portable, to be used in POS, or remotely accessible to be used for distant POS-related activities?

On this basis, we have systemised types of ICT tools and their supporting devices in three main categories which describe where the tool is installed in relation to the open space and how an ICT tool interacts with the user. The subtypes of tools are defined according to POS, user-related functions and specific characteristics. Thus, the developed framework for classifying digital tools for co-creation is addressed in the next section.

References:

- Šuklje Erjavec, I. & Žlender, V. (2020). Categorization of digital tools for co-creation of public open spaces. Key aspects and possibilities. Planning Practice and Research (165-183). In Smaniotto Costa, C., Mačiulienė, M., Menezes, M. & Goličnik Marušić, B. (Eds.). Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice – Reflection – Learning. C3Places Project. Lisbon: Lusófona University Press. https://doi.org/10.24140/2020-sct-vol.4-2.1.

- C3Places. (2019). Methodological Framework for LIVING LABS in European Cities. Available athttps://c3places.eu/outcomes.

- Gehl, J. (2017). Twelve Urban Quality Criteria. Available at https://gehlinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/TWELVE-QUALITY-CRITERIA.pdf

- Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2014). Collaborative projects (social media application): About Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Business Horizons, 57(5), 617–626. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.05.004.

- Participedia. (n.d.). Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- PPS – Project for Public Spaces. (2009). What Makes a Successful Place? Retrieved 10 June 2019. Available at https://www.pps.org/article/grplacefeat.

Methodological Framework for Living Labs for co-creation of public spaces

The methodology proposed for the Project C3Places covers the coordinated implementation of the case studies – each one devoted to different user groups and different types of public spaces – enabling C3Places to reach a wide range of users and urban spaces typology. The case areas identified will give an overview of state-of-art in the interaction between people – places and technology, and will serve as living lab for exploiting new approaches. The Methodological Framework for living labs in European Cities sets the guidelines for application of C3Places framework in 4 national living labs and supports their coordination.

The cases of living labs address communities’ or government initiatives, stakeholders, existing and new ICT-based applications from local and global industrial companies. The data and information collected on selected public open spaces in Belgium, Italy, Lithuania and Portugal enable C3Places to analyse and compare expectations, behaviours and attitudes of different user groups.

The proposed methodology is mainly concerned with assessing and monitoring the impacts and processes before, during, and after the implementation of cases where co-creation plays a vital role. The Methodological Framework consists of the Methodology for Exploring living labs, the Template of living lab Work Plan and the Template of living lab Report.

Through the proposed framework several aspects relevant to assessment and understating of co-creation processes (e.g. collection of data, generalization of gathered data in living lab studies) will be tested and evaluated against the comparability levels.

Co-creation of public open places. Practice – Reflection – Learning

In 17 chapters different invited authors share their experiences in actively involving stakeholders in the production and consumption of public open spaces. With these chapters the Project sparks the discussion on the co-creation for more sustainable, inclusive, attractive and responsive public open spaces. It intends to help researchers, governments and drivers in understanding and implementing more collaborative actions.

The authors share experiences, visions and reflections on how co-creation and participatory processes can open up possibilities for a sustainable and equitable future. This book emphasises three dimensions: practice, reflection, and learning. Practice concerns driving actions, identified and analysed experiences that serve as key models. Reflection refers to exploring and examining the results and performances of a co-creation process. Learning approaches the knowledge transfer and replication induced by the synergy of the different actors involved in this book.

Co-creation of teenagers-sensitive public spaces

Authors: Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Joana Solipa Batista, Marluci Menezes

This paper explores the nexus public spaces – users and co-creation based on the research Project C3Places. The Project, using the potential of co-creation to inspire placemaking, aims to inform decision making to increase the attractiveness, responsiveness, and inclusiveness of public open spaces. It reflects on the results of a case study in Lisbon centered on teenagers as potential co-creators of public spaces, their spatial practices, along with perceptions, needs, and requirements. It also addresses the negotiation of public space by teenagers, the potential of living labs for placemaking and the analysis of local policies and strategies that support civic involvement. The living labs, a central part of this study, were completed prior to Spring 2020, so the research and insights do not reference the global public health crisis caused by COVID-19. This has changed our ordinary everyday life, and the major enduring effect is the way we are allowed to use and move through public spaces. However, when we all are suddenly forced to reconsider our relationship to public spaces, their potential to support a range of inclusiveness becomes even stronger.

Smaniotto Costa, C., Solipa Batista, J., Menezes, M. (2021). Co-Creation of Teenager-Sensitive Public Spaces. The C3Places Project Living Labs in Lisbon, Portugal. Focus, Journal of the City and Regional Planning Department, San Luis Obispo, Ca: Vol. 17: 52-62.

Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies

Author: Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Marluci Menezes

There is an increasing awareness and advocacy claim for engaging the society in the production of public open spaces. This contribution seeks to increase knowledge on the relationship between spaces and the social practices of teenagers, towards a more inclusive and interactive process of public space co-creation. It is based on two European Projects: CyberParks and C3Places, and explores teenagers’ spatial practice and needs, and how to engage them in the process of co-creating more sensitive public spaces, while exploring the challenges and opportunities ICT open. This paper, the results of a case study taking place in Lisbon and the analysis of questionnaires and interviews are discussed.

Smaniotto Costa, C., Solipa, J., Almeida, I., & Menezes, M. (2020). Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies. Cities, vol. 98. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.102574.

The University of Milan contribution to the C3Places Project

Author: R. Pizzi

The presentation at the link describes the idea developed by the UNIMI team: a vibrant new way to create a community that could really communicate and help and grow not only virtually but also in presence *by means* of technology.

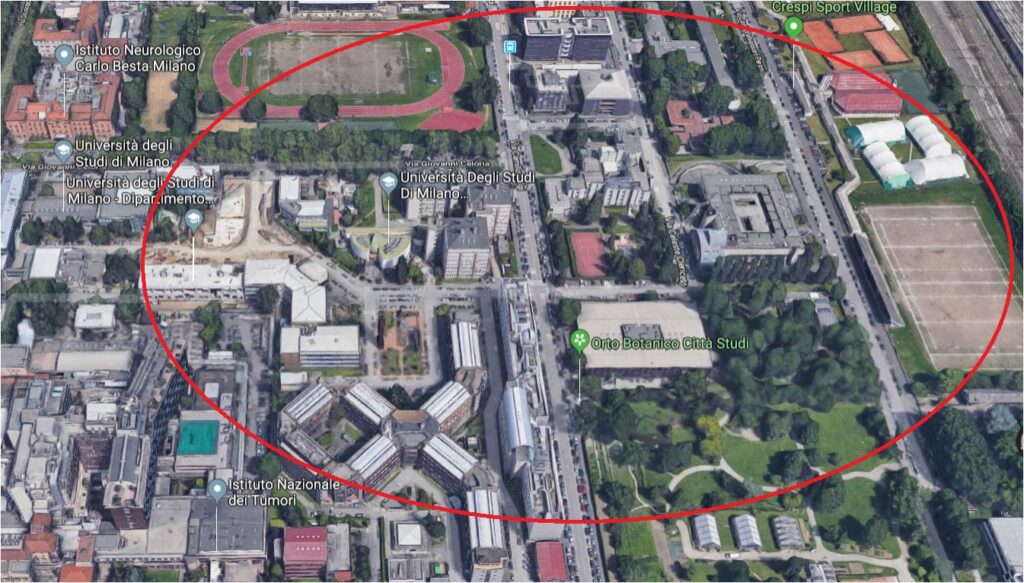

Urban open space can easily become center of shared services and cultural events and opportunities and knowledge (Figure 1).

The availability of public hot spots in public places can be seen as a social service, where digital infrastructures may become a way for the supply of public services, ideas, creativity, opportunities for co-creation and collective cultural and social interchange, promoting sustainability, responsibility and knowledge of nature, the city and citizenship in its cultural diversity.

University of Milan main task in C3Places project was the development of a co-creation platform providing a scientifically validated framework for citizens’ interaction in and with public spaces, leveraging on their diversity potential of co-creation.

A social network built around points of interest of public open spaces, where people can exchange usefule information, moods, requests, ideas.

A complete example has been developed and experiment, yield the novel digital tool to students of the Campus, open also to the citizens living in the area.

Figure 1: View of the “Città Studi” area.

Participatory co-creation and urban sustainability: the role of cooperation in the ICT era

Authors: R. Pizzi, A. Merletti De Palo

In the last decade Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) have become an important tool for socialization. However, living public open spaces firsthand remains fundamental for the development of the cultural identity of a community. ICT allows to develop strategies and tools to increase the quality of public open spaces, positively influencing the co-participatory creation and the effects of social cohesion (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The university area “Città Studi” where the Social Campus points of interest are located.

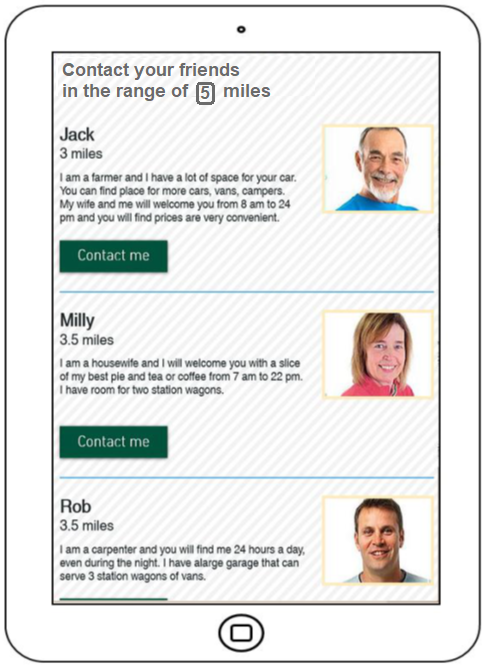

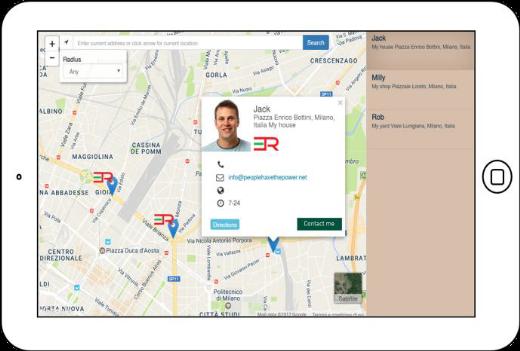

As part of a European research project called C3Places, we intend to generate knowledge and knowhow for a co-creation approach to be used to combine the use of ICT and the studies on cooperation with the essential functions and new potential of the public open spaces (Figures 2 and 3).

We explored the new dynamics of the open spaces as a value-added service for the community, paying attention to the parties interested, to the local context and to the different social groups.

Figure 2: App interface: services and contacts of the private charging points.

Figure 3: The private charging points are geolocalized.

Co-Creazione partecipativa e Sostenibilità Urbana: il Ruolo della Cooperazione nell’Era dell’ICT 2018 / R. Pizzi, A. Merletti De Palo – In: Città Sostenibili / [a cura di] C. Fiamingo, V. Bini, A. Dal Borgo. – Prima edizione. – Broni : Altravista, 2018 Dec. – ISBN 9788899688400.

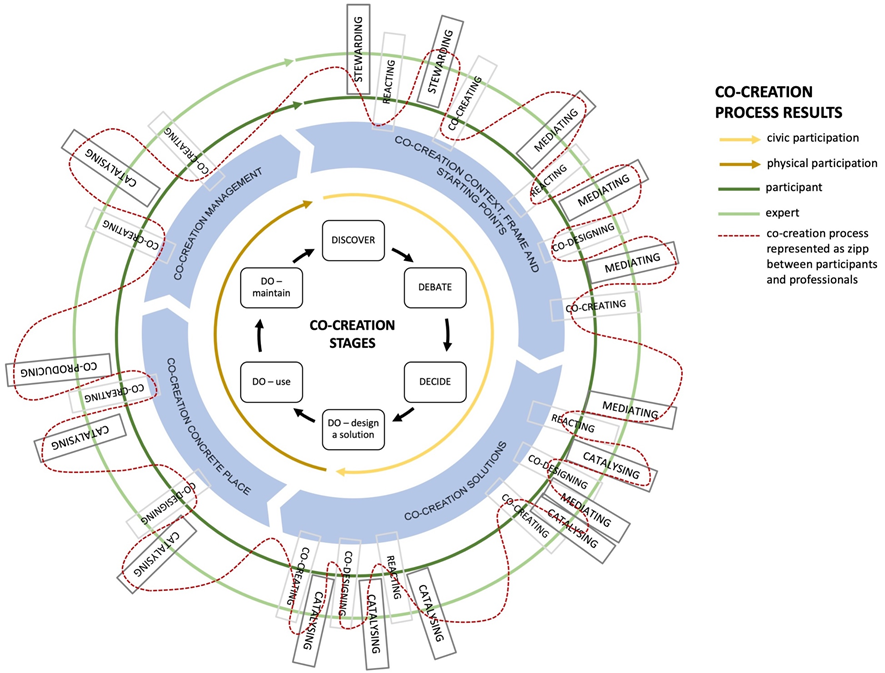

Actors and their roles in the co-creation of Public Open Space

Authors: Barbara Goličnik Marušić, Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Vita Žlender

Despite the agreement in the academic literature that co-creation is a collective creative endeavour (Arnstein, 1969), we believe that the role of citizens and that of professionals differ.

With regard to the roles of citizens, Goličnik Marušić and Šuklje Erjavec (in press) elaborate on three diverse roles of the citizens as co-implementers, co-designers, and co-initiators, of which, only the co-initiator is highly involved in various steps of the contemporary planning process.

With regard to the roles of professionals, scholars use different terms to denote them, ranging from the role of initiator, metadesigner, negotiator, involver and enthusiast (see e.g. Eggertsen Teder, 2019; Vandael et al., 2018).

These roles might overlap with those identified in other literature as facilitator (e.g. Vandael et al., 2018) or a mediator (Goličnik Marušić & Šuklje Erjavec, in press). Different terms used might be a reason for the confusion and the uncomprehensive overview of roles.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the co-creation process needs structure and clearly defined roles, yet it should also remain open to individual suggestions and approaches to enhance the creativity of all parties involved and facilitate constructive problem solving.

We elaborated on the roles in Figure 2.

References:

- Žlender, V, Šuklje Erjavec, I & Goličnik Marušić, B (2020). Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process: Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice. Planning Practice and Research. DOI: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1829286.

- Goličnik Marušić, B., & Šuklje Erjavec, I. (2020) Understanding co-creation within urban open space development process, in: C. Smaniotto Costa, M. Mačiulienė, M. Menezes, & B. Goličnik Marušić. (Eds) Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice—Reflection—Learning. C3Places Project Lisbon: Lusófona University Press. ISBN 978-989-757-125-1. DOI https://doi.org/10.24140/2020-sct-vol.4-1.1.

Co-creation of Public Open Space – challenges and opportunities

Authors: Barbara Goličnik Marušić, Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Vita Žlender

To facilitate the smoothness of a co-creative process, different kinds of participatory tools, methods and technologies have been developed, most of them aiming at being easy to use and available to users anywhere and anytime. Commonly, it is still urban planners who are designing and initiating the process, so the selection of participatory tools mainly depends on them. However, the actors involved in the co-creation and the variety and relationships among them are of crucial importance for the success of the creation process. The relationship between all involved is a partnership, though some literature stresses the communication gaps between various actors involved.

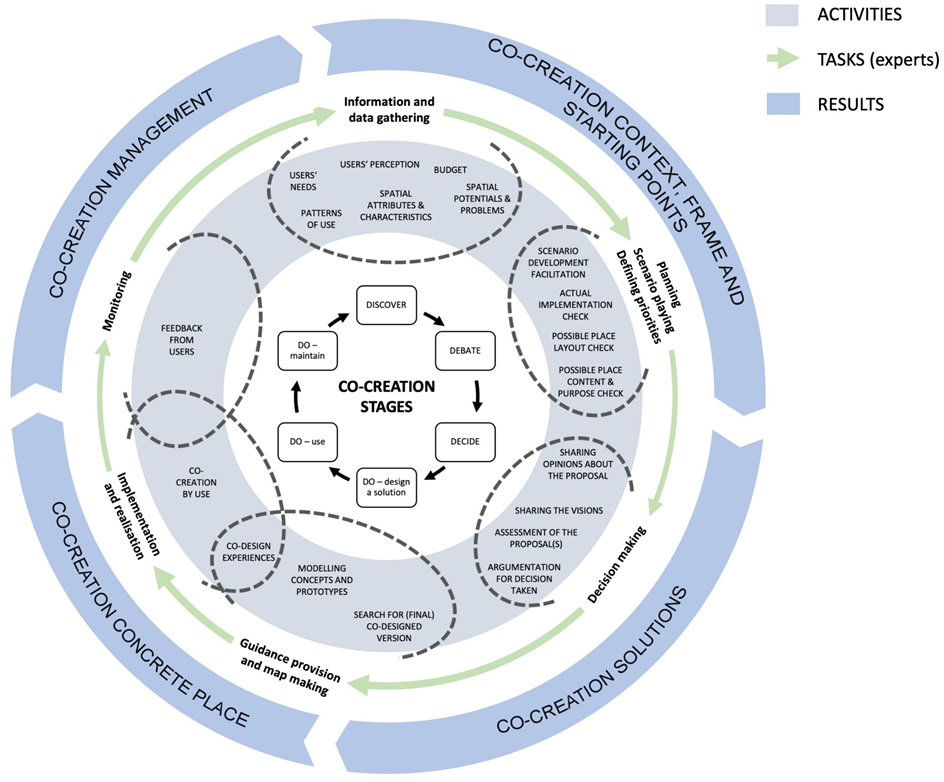

Type of Activities and Tasks of Actors

We defined specific tasks of planning experts and users as the actors involved in the process, and further develop the activities and tasks for each co-creation stage (Figure 1).

Discover. In this phase, activities performed mainly relate to:

- Patterns of use: gathering information about the patterns of how people use a place to provide an overview of behaviours, activities and movements of people in POS;

- Users’ needs: collecting information on citizens’ needs, wishes, preferences, complaints, and more;

- Users’ perception: collecting information on citizens’ perceptions of the environment;

- Spatial potential and problems: information on spatial potentials, problems, obstacles, etc.;

- Using databases: spatial attributes and characteristics information on spatial attributes and other characteristics; and

- Budget: data on budgetary possibilities.

Debate. In the debate phase, most important activities refer to:

- Scenario development facilitation: facilitating the development of the predictions and scenarios to help identify parameters that may impact on people’s use of a POS;

- Actual implementation check: checking financial possibilities and calculations for the implementation and management of different scenarios as possible realisations;

- Possible place layout check: recognizing or understanding place types and their attributes to support the debate about priorities and possibilities once/if implemented; and

- Possible place content and purpose check: recognizing ideas and suggestions shared by the public and other stakeholders about the purpose, vision, aims, possibilities, problems, preferences and priorities of a place once/if implemented

Decide. In this phase, the final decision is met, and the solutions are co-created. Main activities of this phase are:

- Sharing the visions: expressed comments and visions from diverse actors involved;

- Sharing opinions about the proposal(s): opinions about the proposal(s) based on results from the previous phase;.

- Assessment of the proposal(s): appropriateness of the proposed solution(s) against selected criteria; and

- Argumentation for the decision taken: arguing and evaluation steps for decisions taken.

Do. The final phase encompasses co-designing, delivering and implementing a solution, including the actual design use as well as its maintenance as a precondition for the long-term attractiveness and conduciveness for usage. In this phase, the activities may refer to:

- Search for (final) co-designed version: ways for searching for actual co-design solutions;

- Modelling concepts and prototypes: ways for and types of modelling concepts and virtual prototypes;

- Co-design experiences: co-design the site-specific experiences of various actors;

- Co-creation by use: ways of use and types of actual experiences in co-creation according to use; and

- Feedback from users: gathering feedback from users.

References:

- Žlender, V, Šuklje Erjavec, I & Goličnik Marušić, B (2020). Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process: Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice. Planning Practice and Research. DOI: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1829286.

- Goličnik Marušić, B., & Šuklje Erjavec, I. (2020) Understanding co-creation within urban open space development process, in: C. Smaniotto Costa, M. Mačiulienė, M. Menezes, & B. Goličnik Marušić. (Eds) Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice—Reflection—Learning. C3Places Project Lisbon: Lusófona University Press. ISBN 978-989-757-125-1. DOI https://doi.org/10.24140/2020-sct-vol.4-1.1.

- Šuklje Erjavec, Ina, and Ruchinskaya, Tatiana (2019). A Spotlight of Co-Creation and Inclusiveness of Public Open Spaces. In CyberParks – The Interface Between People, Places and Technology, edited by Smaniotto Costa C. et al. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11380. Springer, Cham.

Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process. Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice

Authors: Vita Žlender , Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Barbara Goličnik Marušić

This research aimed to explore information and communication technologies (ICT) types to support co-creation activities in public open spaces (POS) at different stages of the co-creation process.

We conducted state-of-the-art research on the methods, best practices, obstacles and potential of ICT tools and co-creation activities to ease the interaction between stakeholders engaged in the process.

Based on those findings, we proposed an ICT tools selection framework. Four living labs were analysed to better understand the practical side of digitally aided co-creation.

We conclude by exposing challenges and suggest ways to move forward toward genuinely digitally supported co-creation of the POS.

Vita Žlender , Ina Šuklje Erjavec & Barbara Goličnik Marušić (2020): Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process: Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice, Planning Practice & Research, DOI: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1829286

Mapping Digital Co-Creation for Urban Communities and Public Places

Authors: Monika Mačiulienė

Increasingly digital communication, social media and computing networks put the end-users at the center of innovation processes, thus shifting the emphasis from technologies to people. In the private sector, this shift to user-centricity has been conceptualized under such approaches as Service-Dominant Logic and Open Innovation 2.0.

Public sector conceptualizes the change through the New Public Governance and Open Government paradigms and suggest that the public value is no longer created by the governments alone but in collaboration between the public entities, private sector, civil society organizations and citizens.

While traditional approaches to public engagement and governmental transformations remain relevant, this article focuses on the growing potential of networked urban communities to solve the social problems. It expands the co-creation research field and suggests a typology discerning co-creation patterns when enhancing the public spaces with a community-wide participation with the use of creative, innovative and cooperative Information and Communication Technologies’ applications.

The sample for web-based monitoring consists of 10 digital applications linked with design and improvement of public spaces in Vilnius, Lithuania. The proposed typology framework gives an overview of the state-of-art in the interaction between people, places and technology. The research helps to discern how different technological, organizational and other social factors influence and shape the patterns of co-creative initiatives.

Mačiulienė, M. (2018). Mapping Digital Co-Creation for Urban Communities and Public Places. Systems, 6(2), 14. doi:10.3390/systems6020014

Types of ICT tools

Authors: Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Vita Žlender

The development of digital technologies opened new opportunities for different collaborative processes, many new possibilities to engage and activate people, and for new ways of interacting with the environment. On the basis, of the possible use of different ICT tools in the relation to the type of function and way of integration in the process of planning and design, place making, place management and community engagement. We have systemised types of ICT tools and their supporting devices according to location of the tool in the relation to the open space and the way of its interaction with the user. In that was we defined three main categories:

- Place-located ICT tools

- Portable ICT tools

- Remotely accessible ICT tools

Each category is also structured into the subtypes of tools, which are defined according to POS, user-related functions and specific characteristics. The subtypes of tools are defined according to the POS and user-related functions and specific characteristics.

Place-located ICT tools

These tools are located ‘in place’ and installed as a part of physical features of POS. Such digital tools add new functions into existing place or are part of the design of the new one, combining digital and physical layers into a new hybrid use. The overview of place located ICT tools is presented in the following table.

| Type | Subtype |

| Individual digital elements as new types of equipment in POS | Digital public displays Public interactive displays Multimedia interactive elements Multifunctional tech totems Interactive and responsive sound installations Responsive lighting elements Multimedia pavilions Interactive POS elements: a combination of different digital elements (e.g. screens + speakers + lighting) as artistic installations per se or frames for them, responsive sculptures and fountains, play equipment, etc. Individual elements for energy provision, as electric vehicle charging stations, solar energy stations, etc. |

| Digital part(s) of POS equipment or parts of surrounding buildings and equipment | Digital elements upgrading or supporting the functioning of urban elements (these are incorporated into traditional types of POS furniture like bench, table, fence, light, playing or sport equipment, etc.) Digital additions for upgrading the functioning, maintenance or experience of the area like WI-FI hotspot, speakers, QR codes, sensors, beacons, universal intelligent nodes Elements for energy provision to support use of portable ICT devices that are incorporated into traditional types of POS furniture, playing or sports equipment, etc.) in a form of plugs, solar panels, etc. Media facades as part of other built structures, e.g. facades, walls, etc. Projection mapping (Digital projectors) Digital projectors as part of other built structures, e.g. facades, grounds, walls, etc. SAR (spatial augmented reality) systems: – Shader lamps (projector-based augmentation) – Mobile projectors – Virtual tables – Smart projectors (projection mapping), etc. |

| Responsive materials | Adaptive pavements (adapting to the weather, accessibility needs, etc.) Responsive verticals (changing by touch, sound, etc.) Measuring materials (for monitoring the use, conditions, etc.) Self-cleaning, self-repairing and materials |

Portable ICT tools

These tools bring a user to the public open space and establish a relationship with space, other users and/or other premises. Their main purpose for POS development and co-creation is to develop new forms of uses and activities in POS by extending human abilities, i.e. adding a digital sense to five basic human senses and to support a direct feedback of users for better POS development and management. Their structure is presented in the following table.

| Type | Subtype |

| Smart devices | Smartphones and tablets Smart glasses (e.g. Google Glasses) Smart grid Smart watches (e.g. iWatch), etc. |

| Place related mobile APPS | Directly supporting learning about place and its natural and manmade characteristics, adding to the experience of place, support moving through it, activity and movement tracking) Collect and share data on environmental conditions, evaluate conditions, etc. Directly support place evaluation and feedback VR and AR apps for opinion and proposal development and sharing, etc. Other apps are discussed within web platforms and apps (Table 3) |

| GPS -positioning devices | Individual or as part of other smart devices |

| Other personal VR and AR devices | Head-mounted displays (e.g. headsets, eyeglasses, contact lenses) Multi-projected environments Combination with physical environments or props (e.g. 3D mouse, the wired glove, motion controllers, optical tracking sensors) |

| Cameras, recorders | Many different options |

| E-textiles – aesthetic and performance enhancing | Smart garments, smart clothing, smart textiles, or smart fabrics providing the added values to the wearer, enabling the interaction with the environment and responsiveness to the personal activities and condition Wearable computing with microcontrollers, sensors and actuators |

| Digital health and fitness tools | Devices and apps to encourage healthy habits, fitness and other physical activity tracking, health measurements, Internet connected fitness systems, Environment quality sensors and alarm systems |

Remotely accessible ICT tools

This group encompasses, on the one side, a broad variety of ICT tools such as laptops, PCs, screens, mobile phones and other hardware, and on the other, web platforms and apps used for digitally networked interactions such as distant society engagement, public consultation, information and opinion collection, exchange and sharing, voting, etc. Their general advantage is that they can at one time reach a much larger number of people who can also choose their own time of use.

In the structure we focus on aspects that are very important to support different co-creation activities for POS development, such as preparation, discovering, debating, deciding, designing, implementation, maintenance, use, and monitoring of public open spaces. The following table provides a general overview on how different components and tools enable and support different dimensions of remote public involvement.

| Type of components / tools | Examples |

| Social networking platforms and sites | Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram |

| Static web sites | Professional portfolios, digital curriculums |

| Blogs and microblogs | WordPress, Joomla, Drupal, Twitter |

| Tools for social bookmarking, tagging | Tools for social bookmarking, tagging |

| Online storage (cloud storage, file synchronisation, personal cloud) | Dropbox, GoogleDrive, iCloud |

| Social network aggregation | Hoot Suite, FriendFeed |

| Encyclopaedia | Wikipedia |

| Survey | Google Forms, SurveyHero, Typeform, SurveyMonky, InvolveMe |

| Content communities – Online databases of multimedia content, that allow users to share online multimedia materials by photo, video, podcasts, presentations, etc. | Flickr, SmugMug, Picasa, GigaPan Youtube, Vimeo iTunes SlideShare, VoiceThread |

| Internet forum / Message board Textboards and Imageboards | Quora, SkyscrapperCity |

| Chat rooms in the form of Web conferencing, Video conferencing, etc. Instant messaging | Facebook Messenger, Gmail messenger, WhatsApp |

| Electronic mailing list, news group | Mailing lists of different organisations, companies, institutions, etc. |

| Online dictionaries | Urban Dictionary |

| WEB GIS – Analytical – Animated and real-time – Collaborative (e.g. PPGIS) – Online atlases, etc. | Open Street Map, Google maps, Apple maps, and many different projects specific and city specific data collection platforms |

| Web-based simulation platforms and apps for discrete events, continuous events, etc. | Digital participatory platforms: Mobility Testbed, Commonplace, coUrbanize, TransformCity, etc. |

| Construction and management simulation games, e.g. city building games | Lincity, SimCity, etc. |

| Augmented reality apps | Pokemon GO, ScentExplore |

| Virtual social worlds | Second life |

Reference:

Potentials and bottlenecks in digital co-creation with teenagers

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

C3Places Lisbon Living Lab allowed to reflect on the potential and bottlenecks in digital co-creation with teenagers. The labs revealed the importance, of clear messages, goals and expectations, shared from the beginning.

Such messages have to encompass what is going to happen, why is it happening, when each task has to be performed, which results are expected and what are the benefits for participants.

In Lisbon, the labs revealed teenagers’ have a weak urban literacy and low spatial representation skills, and difficulties in identifying own needs and expressing ideas for public spaces, but the theme sparks interest in most of them and the interactive activities provide a forum for learning about urban space and share experience of teenagers use of space and needs.

For this reason is important to assess the knowledge, abilities and motivations of the target participants, and harness their full potential to actively participate in co-creation of public open spaces. To assess the success rate and overall satisfaction with the labs, a short questionnaire was distributed at the end of the last session asking students to indicate the perceived learning effect. The results flutuate between a high satisfaction and a disatisfaction, in line with the general observation made during all sessions; while a group of students showed interest and conducted lively the discussion, another small group remained apart, even not reacting to a direct request to express their ideas or opinions.

While in the questions related to personal experience with collaboration and exchange of ideas, the agreement with statements was low, the ones related to learning effect by taking part of the workshops the agreement was higher.

This can be analysed as a positive benefit for increased knowledge gained by this type of participative methodology.

In this respect, it is noted that the living labs were inserted in the daily school activities, and the school board selected the classes that participated in the two phases.

The willingness and readiness to get involve in digital co-creation may be different than when students can choose on their own to participate.

The second phase of labs with teenagers tested the potential of using digital devices in co-creation of public open spaces. Tablets were provided for the participants and facilitators recommended the use of digital tools for collection and discussion of ideas and general group work.

The use of this devices may be benefitial to allow for more interactivity in co-creation. For digital co-creation, devices and tools should be provided and integrated in the proccess, efficiently and logically.

In Lisbon, results highlight a important role of digital co-creation to increase the awareness on placemaking and provide opportunities for teenagers (and other groups) to discuss different needs on public spaces. That discussion is a crucial one in urban planning, since public spaces are common goods and everyone should be able and encouraged to use them and share them with others.

C3Places Lisbon

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

C3Places in Lisbon implemented living labs on urban planning and design targeting teenagers in Alvalade neighbourhood.

The labs were developed for co-creative and collaborative practice, exploring opportunities for a direct involvement of teenagers in placemaking, providing a platform for learning and free expression of values and ideas about and for urban fabric.

The methodology encompassed different tools, such as thematic workshops, exploratory site visits in the neighbourhood, discussions and debates sessions and questionnaires, focused on teenagers’ practices, uses and needs on public open spaces.

The living labs were implemented in two phases.

A pilot phase was organised between February and May 2018 with two 10th grade classes (N=49 students, aged 15 to 18), consisting in total of 24 hours intervention per class, with both indoor and outdoor activities, aimed at discussing the city and its production.

A methodological decision was made by the researchers on which data should be analysed in more depth. Materials as questionnaires and the facilitators observational notes, as direct tools for data collection, were prioritized. Questionnaires had closed questions, analysed quantitively, and open questions, analysed through thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Other data resulting from materials that provided support for the activities and exercises complemented and reinforced these analyses.

The second phase, a week-long lab was organised in May 2019 with two classes of the first year of professional training education (N=20, aged 16 to 18). The students developed and justified design proposals for the space in front of their school.

The labs were organised in four sessions of 1,5 hour each with an emphasis on group work and on the use of digital tools (Padlet, image bank, presentation programmes and Google Maps).

The facilitators observational notes, a questionnaire to assess importance of co-creation and the teenagers’ proposals presented by teenagers analysed. Living labs were complemented with other methods of data collection, as space observations and interviews with experts. Space observations enabled to obtain an overview of the whole neighbourhood, as well as a more focused outline on public spaces used by teenagers.

Two sets observations were conducted, undertaken at different periods of the day and different days of the week. Descriptive notes and an image library enriched the field work.

The first set of observations consisted of mapping out the local public spaces.

In the second set, the Marquês de Soveral Street, where the school is located, and well known and used space by the teenage students, was selected for detailed observations (during a twenty-day period).

Data were collected with the aid of two distinctive observation grids. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with the four planning experts working with public space issues at the Junta de Freguesia de Alvalade (parish council). The quality of the analysis is secured through several steps, such as: familiarization with the data; generating initial codes which were then aggregated into potential themes; initial themes review, and identifying final themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

References:

The C3Places mobile application

Authors: Inês Almeida, Joana Batista, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

Developing and testing of a mobile application to support research activities is one of the goals of the C3Places Project. The C3Places application is designed to enable researchers to address questions related to the use of public spaces via digital technology. A relevant aspect of the digital and mobile technologies lies in their possibility to enhance communication with prospective users, hence enabling possibilities for creative participation in placemaking and co-creation.

The C3Places application consists of two main components: a web service (web platform) and the smartphone application (app) and is enabled to be used anywhere in the world.It allows researchers to collect evidence base and demonstrate the social values of public spaces – backed by users’ opinion and views. Also, by providing evidence and demonstrating that public space is having a positive societal impact can increase the enthusiasm for more inclusive and responsive public spaces.

By collecting such data, the C3Places App contributes to better explore and more precisely research on public space practices, as well integrate the use and point of view of several users on different spaces. Another interesting feature lies in the possibility to collect the weather conditions automatically, therefore researchers can also reflect on how weather conditions affect (or not) the usage of public open spaces.

Finally, considering that it is up to the researcher to create the questions or the photo questionnaire, the possibilities are infinite and can be addressed directly to each research topic that is being carried out. So, the C3Places app allows scholars and researchers to make more specific or broader public open space research and, since it runs in Android operative system, the range is quite extensive. The use of the C3Places App is free and can be requested at c3places.coordination@ulusofona.pt.

The manual for preparing a research subject with the help of the C3Places App can be downloaded here.

ICT-Based Participatory Co-Creation of Urban Sustainability

Author: Rita Pizzi

In recent times Information and communication technologies (ICT) have become an important tool for socialization. More and more people build and maintain relationships through various social media and increasingly this influences the way they organize their daily lives and how they use the city and its spaces. However, the quality of public open spaces remains fundamental for the development of the cultural identity of a community, as they are important gathering points in the urban fabric and offer occasion for interactions and collaborations between generations and different ethnic diversities. People of all ages still need contact with nature and with other people, in order to develop different life skills, values, attitudes to health, satisfaction with their lives and responsibility towards the environment. ICTs allow the development of strategies and tools to increase the quality of public open spaces, positively influencing participatory co-creation and the effects of social cohesion. New ways of cooperative co-creation must be considered, in particular by using ICT to facilitate community interaction and engagement for the integration of diversity, and identifying social needs in open public spaces, aiming at the development of vibrant and accessible urban communities.ICT gives also the opportunity to the urban communities to improve sustainability.This paper presents best practices and new ICT solutions for enjoyable, inclusive, participatory, sustainable urban spaces.

ICT-based Participatory Co-Creation of Urban Sustainability / R.M.R. Pizzi. – In: INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF COMPUTER APPLICATIONS. – ISSN 0975-8887. – 182:30(2018 Dec), pp. 30-35.