Partners:

Universidade Lusófona, Interdisciplinary Research Centre for Education and Development

LNEC – National Laboratory of Civil Engineering

Lisbon Living Lab

The Lisbon Living Lab will be centred on teenagers (young people 13 to 17 years of age) as they are a particular age group with specific needs and interests on public spaces, the relationship between teens and public spaces is very intrinsic, as public spaces may serve as a fundamental (play)ground for teenagers’ development.

The Lisbon’s Alvalade neighbourhood will be living lab to explore how teenagers use and behaviour in urban fabric and what are they needs and preferences on public open spaces. The main objective is to engage teenagers in a process of the co-creation of urban spaces, by exploring the leading research question: “How can we capitalise on teenagers’ new-found love of the wired life (Thomas, 2013) to encourage them to be more outdoors?”

Co-creation of teenagers-sensitive public spaces

Authors: Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Joana Solipa Batista, Marluci Menezes

This paper explores the nexus public spaces – users and co-creation based on the research Project C3Places. The Project, using the potential of co-creation to inspire placemaking, aims to inform decision making to increase the attractiveness, responsiveness, and inclusiveness of public open spaces. It reflects on the results of a case study in Lisbon centered on teenagers as potential co-creators of public spaces, their spatial practices, along with perceptions, needs, and requirements. It also addresses the negotiation of public space by teenagers, the potential of living labs for placemaking and the analysis of local policies and strategies that support civic involvement. The living labs, a central part of this study, were completed prior to Spring 2020, so the research and insights do not reference the global public health crisis caused by COVID-19. This has changed our ordinary everyday life, and the major enduring effect is the way we are allowed to use and move through public spaces. However, when we all are suddenly forced to reconsider our relationship to public spaces, their potential to support a range of inclusiveness becomes even stronger.

Smaniotto Costa, C., Solipa Batista, J., Menezes, M. (2021). Co-Creation of Teenager-Sensitive Public Spaces. The C3Places Project Living Labs in Lisbon, Portugal. Focus, Journal of the City and Regional Planning Department, San Luis Obispo, Ca: Vol. 17: 52-62.

Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies

Author: Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Marluci Menezes

There is an increasing awareness and advocacy claim for engaging the society in the production of public open spaces. This contribution seeks to increase knowledge on the relationship between spaces and the social practices of teenagers, towards a more inclusive and interactive process of public space co-creation. It is based on two European Projects: CyberParks and C3Places, and explores teenagers’ spatial practice and needs, and how to engage them in the process of co-creating more sensitive public spaces, while exploring the challenges and opportunities ICT open. This paper, the results of a case study taking place in Lisbon and the analysis of questionnaires and interviews are discussed.

Smaniotto Costa, C., Solipa, J., Almeida, I., & Menezes, M. (2020). Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies. Cities, vol. 98. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.102574.

Potentials and bottlenecks in digital co-creation with teenagers

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

C3Places Lisbon Living Lab allowed to reflect on the potential and bottlenecks in digital co-creation with teenagers. The labs revealed the importance, of clear messages, goals and expectations, shared from the beginning.

Such messages have to encompass what is going to happen, why is it happening, when each task has to be performed, which results are expected and what are the benefits for participants.

In Lisbon, the labs revealed teenagers’ have a weak urban literacy and low spatial representation skills, and difficulties in identifying own needs and expressing ideas for public spaces, but the theme sparks interest in most of them and the interactive activities provide a forum for learning about urban space and share experience of teenagers use of space and needs.

For this reason is important to assess the knowledge, abilities and motivations of the target participants, and harness their full potential to actively participate in co-creation of public open spaces. To assess the success rate and overall satisfaction with the labs, a short questionnaire was distributed at the end of the last session asking students to indicate the perceived learning effect. The results flutuate between a high satisfaction and a disatisfaction, in line with the general observation made during all sessions; while a group of students showed interest and conducted lively the discussion, another small group remained apart, even not reacting to a direct request to express their ideas or opinions.

While in the questions related to personal experience with collaboration and exchange of ideas, the agreement with statements was low, the ones related to learning effect by taking part of the workshops the agreement was higher.

This can be analysed as a positive benefit for increased knowledge gained by this type of participative methodology.

In this respect, it is noted that the living labs were inserted in the daily school activities, and the school board selected the classes that participated in the two phases.

The willingness and readiness to get involve in digital co-creation may be different than when students can choose on their own to participate.

The second phase of labs with teenagers tested the potential of using digital devices in co-creation of public open spaces. Tablets were provided for the participants and facilitators recommended the use of digital tools for collection and discussion of ideas and general group work.

The use of this devices may be benefitial to allow for more interactivity in co-creation. For digital co-creation, devices and tools should be provided and integrated in the proccess, efficiently and logically.

In Lisbon, results highlight a important role of digital co-creation to increase the awareness on placemaking and provide opportunities for teenagers (and other groups) to discuss different needs on public spaces. That discussion is a crucial one in urban planning, since public spaces are common goods and everyone should be able and encouraged to use them and share them with others.

Brief notes on user’s participation in public spaces planning and design

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

For C3Places a public space must be inclusive and responsive, allowing people to use it without restrictions and to fulfil socio-spatial needs. To achieve more inclusive and responsive spaces, users should have a voice in the process of planning and design, also known as placemaking (PPS, n. d.).

Engaging people actively calls for appropriate methodologies as inclusive design (Carmona, Heath, Tiesdell, & Oc, 2003) or co-creation, the last is at the core of C3Places research.

C3Places uses the terms inclusive and responsible place to describe a far-reaching framework of principles and best-practice on which communities can build a shared commitment to sustainability in social and urban development. For that, communities should be engaged in the making and transforming of public spaces from the very beginning.

Public space as a shared common good is the fundamental premise – public space is a resource which, if used responsibly, can help transform the way people live, work, recreate, and interact. In placemaking, stakeholders should have a clear understanding on how specific characteristics and shapes affect the experience of the space (Alves, 2005; Stevens, 2007).

Therefore, interested parties as different users’ groups, community facilitators, professionals, local authorities and municipalities, should be engaged directly, their opinions accounted for and their needs responded to by placemaking (Alves, 2005; Carmona et al., 2003; Thompson, 2002; UN-Habitat, 2015).

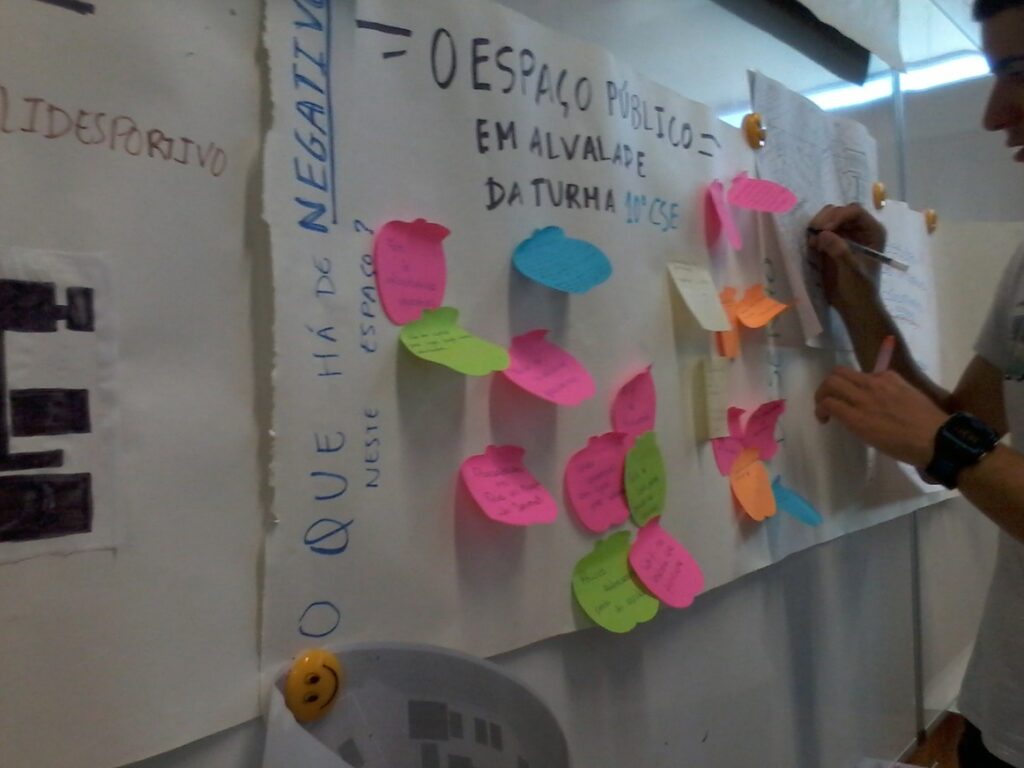

The case-study in Lisbon followed this recommendation and different stakeholders were brought together in the development and operationalisation of Living Labs (Figures 1 and 2) (Smaniotto-Costa, Almeida, Batista & Menezes, 2018).

Figure 1: Living Lab Lisbon – brainstorming exercise with participants to reflect on characteristics of and ideal public space. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2018)

Participative approaches bring challenges of different sorts: in terms of time to be invested, human resources, monitoring and structuring the process that may impose demands that are too high for planners and authorities to see the advantages; in deciding who to involve; the time offset between participation in the process and benefitting from the outcome may be too long for users to engage and, due to transitory needs of users’, too stretched to provide a response while the changes are still valid; questions may be considered too technical or complex for the comprehension of non-professionals and; participation may add a legitimacy to the process but without truly respecting the opinions and ideas of those involved (Alves, 2005; Jupp, 2007; Talen, 2000; Valentine, 2004).

Figure 2: Living Lab Lisbon – group work to draw ideas and proposals for transformation of a public open space. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2019)

However, creating collaborative environments for planning, designing and transforming public spaces is fundamental for a placemaking process more interactive and able to meet the needs of the community, and to produce public places that are more attractive, meaningful, inclusive and sustainable.

Co-creation, as an open process with no previous fixed results, is a challenge for all parts involved but it is at the same time an open door for innovative ideas and solutions. In co-creation a broader range of people come together around the same table to negotiate and reconcile their different needs and interests, solve problems, freely express their concerns and expectations and, ideally, foster a community around public spaces ensuring more sustainable use (Figure 3).

The experiences gained within C3Places in the Living labs in Ghent, Lisbon, Milan and Vilnius are described at the site MyC3Place.

Figure 3: Living Lab Lisbon – outdoor exercise for participants to observe and discover different public open spaces. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2018)

References:

- Alves, F. B. (2005). O Espaço Público Urbano. Qualidade, Avaliação e Participação Pública. Porto: Escola Superior Artística do Porto.

- Carmona, M., Heath, T., Tiesdell, S., & Oc, T. (2003). Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. Michigan: Architectural Press.

- Jupp, E. (2007). Participation, local knowledge and empowerment: Researching public space with young people. Environment and Planning A, 39(12), 2832–2844.

- PPS – Project for public spaces. (2017) The Placemaking Process.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Almeida, I., Batista, J., Menezes, M. (2018). Envolver adolescentes no pensar a cidade: reflexão sobre oficinas temáticas de urbanismo no Bairro de Alvalade, Lisboa. Engaging teenagers in placemaking: Reflections on thematic workshops in urban planning in Lisbon’s Alvalade Neighbourhood. Revista de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território (GOT), 15, 117-142, (in Portuguese).

- Stevens, Q. (2007). The Ludic City. London and New York: Routledge.

- Talen, E. (2000). The Problem with Community in Planning The Problem with Community, 15(2).

- Thompson, C. W. (2002). Urban open space in the 21st century. Landscape and Urban Planning, 60(2), 59–72.

- UN-Habitat. (2015). Adequate Open Public Space in Cities. A Human Settlements Indicator for Monitoring the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda.

- Valentine, G. (2004). Public space and the culture of childhood. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Brief notes on social value of public spaces

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

Public space is here conceptualised following UN-Habitat (2015, 15) as “all places publicly owned or of public use, accessible and enjoyable by all for free and without profit motive”. Among them are streets, squares, plazas, marketplaces, parks, green spaces, greenways, community gardens, playgrounds, waterfronts, urban forests and agricultural used land. C3Places research focus only on urban public open spaces.

Public spaces have been idealised as democratic domains, places of inclusiveness where is possible to be among friends and strangers, encounter differences and engage in planned or serendipitous interactions (Innerarity, 2006). Central to a city well-being, public spaces contribute to the quality of urban life, fostering social, cultural and economic capital (UN-Habitat, 2016). A vast body of literature focus on their social function (Figure 1), as providers of the place for peoples’ interaction with other people (Carmona, Heath, Tiesdell, & Oc, 2003; Gehl, 1987; Innerarity, 2006; Jacobs, 1961; Lefebvre, 1991; Sennett, 1977) and with their environment (Smaniotto & Menezes, 2016). Public spaces act as stage for the enactment of citizenship, to practice publicness, and as such they play a key role within the complex social infrastructure (Smaniotto Costa & Menezes, 2016). Societies’ differences and similarities are put on display in public spaces, allowing distinct groups to claim their right to appropriate particular places and manifest their sense of belonging to society (Innerarity, 2006; Mitchell, 1995). Public spaces enable symbolic identification (Carmona et al., 2003), they are the places where social and cultural identities and the individuals’ role in their community are negotiated, and this may foster the context for mutual understanding and respect, enabling the development of social bonds. Yet, historically, public space was also the site where power structures manifested themselves and dominant social and moral orders were produced, imposed and perpetuated (Sennett, 1977).

Moreover, those public spaces covered by plants and with soft surfaces (Figure 2) offer further environmental benefits as they improve the urban environmental quality (such as air purification, water storage, CO2 sequestration) and provide space for leisure and recreational activities (Smaniotto Costa, Suklje Erjavec, & Mathey, 2008).

They offer also further benefits for public mental health (Muñoz, 2009) and for decreasing in contemporary health problems as obesity and sedentarism (Godbey, 2009). Jacobs (1961) and Gehl (1987) drew attention to the importance of putting people at the centre of public space, analysing how people appropriate specific places, what are their spatial practises and needs towards creating better and more inviting public spaces.

C3Places following those premisses is analysing how specific users – teenagers or elderly – appropriate urban public open spaces and how they can be better configurated to respond to different needs. In Lisbon, observations seem to indicate that urban public spaces of transit, as streets (Figure 3), are used mainly for matters of convenience and proximity to primary spaces of daily significance as the home and the school (TBA).

References

- Carmona, M., Heath, T., Tiesdell, S., & Oc, T. (2003). Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. Michigan: Architectural Press.

- Gehl, J. (1987). Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Godbey, G. (2009). Outdoor Recreation, Health, and Wellness: Understanding and Enhancing the Relationship. Recreation, May 2009, 1–42.

- Innerarity, D. (2006). O novo espaço público. Lisboa: Teorema.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and life of Great American Cities. New York and Toronto: Vintage Books – Random House.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Production.

- Mitchell, D. (1995). The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy. Annals of the Association of American Geographers.

- Muñoz, S.-A. (2009). Children in the Outdoors: A literature Review. Forres: Sustainable Development Research Centre.

- Sennett, R. (1977). The Fall of Public Man. London: Penguin Books.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Menezes, M. (2016). A agregação das tecnologias de informação e comunicação ao espaço público urbano. Reflexões em torno do projeto CyberParks – COST TU 1306. urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana (Brazilian Journal of Urban Management), 8 (3): 332-344. Doi: 10.1590/2175-3369.008.003.AO04.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Šuklje Erjavec, I., Kenna, T., de Lange, M., Ioannidis, K., Maksymiuk, G., de Waal, M. (Eds.) (2019): CyberParks – The Interface Between People, Places and Technology – New Approaches and Perspectives. Cham: Springer, Series: Information Systems and Applications LNCS 11380. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-13417-4.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Suklje Erjavec, I., & Mathey, J. (2008). Green Spaces – a Key Resources for Urban Sustainability. The GreenKeys Approach for Developing Green Spaces. Urbani Izziv, 19(2 Mestne zelene površine / Urban green spaces), 199–211.

- UN-Habitat. (2015). Adequate Open Public Space in Cities. A Human Settlements Indicator for Monitoring the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda.

- UN-Habitat. (2016). New Urban Agenda: Quito Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All. In Habitat III Conference (p. 24). United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

Loom of Ideas

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

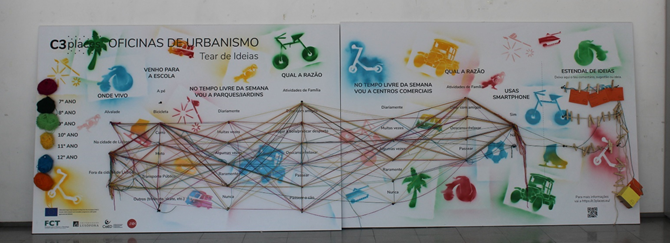

As a way to engage a higher number of students in a reflection on the use and quality of the space in front of the school, a visually attractive and interactive board – called Loom and Clothesline of Ideas (Figure 1).

The Loom was developed to encourage a broad participation of students identifying spatial qualities and problems and stands in the school hall from May to July 2019. It had seven multiple choice questions displayed in columns (place of living, mode of transportation from home to school, frequency of public open space use for leisure, the activities performed, use of commercial places in free time and reason for it and use of smartphone).

A nail indicated the place for each possible answer. For each school grade different coloured woollen yarns hanged next to the questions (the school has grade 7 to 12). To provide their answer the students should wrap the yarn around the corresponding nail (altogether 56 answers were collected) (Figure 2).

In the clothesline students could write down in cards comments, suggestions or ideas and hung them in the line (Figure 3).

Altogether 35 cards were collected. Two main issues raised from the cards: the request for more sitting facilities in the school yard and around the school, and the call for more outdoor activities.

Yet, placemaking can only make a direct contribution for the first issue, but on the flip side, when the outdoor conditions are more suitable, the second call – more outdoor activities – can be easier accomplished.

C3Places Lisbon

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

C3Places in Lisbon implemented living labs on urban planning and design targeting teenagers in Alvalade neighbourhood.

The labs were developed for co-creative and collaborative practice, exploring opportunities for a direct involvement of teenagers in placemaking, providing a platform for learning and free expression of values and ideas about and for urban fabric.

The methodology encompassed different tools, such as thematic workshops, exploratory site visits in the neighbourhood, discussions and debates sessions and questionnaires, focused on teenagers’ practices, uses and needs on public open spaces.

The living labs were implemented in two phases.

A pilot phase was organised between February and May 2018 with two 10th grade classes (N=49 students, aged 15 to 18), consisting in total of 24 hours intervention per class, with both indoor and outdoor activities, aimed at discussing the city and its production.

A methodological decision was made by the researchers on which data should be analysed in more depth. Materials as questionnaires and the facilitators observational notes, as direct tools for data collection, were prioritized. Questionnaires had closed questions, analysed quantitively, and open questions, analysed through thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Other data resulting from materials that provided support for the activities and exercises complemented and reinforced these analyses.

The second phase, a week-long lab was organised in May 2019 with two classes of the first year of professional training education (N=20, aged 16 to 18). The students developed and justified design proposals for the space in front of their school.

The labs were organised in four sessions of 1,5 hour each with an emphasis on group work and on the use of digital tools (Padlet, image bank, presentation programmes and Google Maps).

The facilitators observational notes, a questionnaire to assess importance of co-creation and the teenagers’ proposals presented by teenagers analysed. Living labs were complemented with other methods of data collection, as space observations and interviews with experts. Space observations enabled to obtain an overview of the whole neighbourhood, as well as a more focused outline on public spaces used by teenagers.

Two sets observations were conducted, undertaken at different periods of the day and different days of the week. Descriptive notes and an image library enriched the field work.

The first set of observations consisted of mapping out the local public spaces.

In the second set, the Marquês de Soveral Street, where the school is located, and well known and used space by the teenage students, was selected for detailed observations (during a twenty-day period).

Data were collected with the aid of two distinctive observation grids. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with the four planning experts working with public space issues at the Junta de Freguesia de Alvalade (parish council). The quality of the analysis is secured through several steps, such as: familiarization with the data; generating initial codes which were then aggregated into potential themes; initial themes review, and identifying final themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

References:

The C3Places mobile application

Authors: Inês Almeida, Joana Batista, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

Developing and testing of a mobile application to support research activities is one of the goals of the C3Places Project. The C3Places application is designed to enable researchers to address questions related to the use of public spaces via digital technology. A relevant aspect of the digital and mobile technologies lies in their possibility to enhance communication with prospective users, hence enabling possibilities for creative participation in placemaking and co-creation.

The C3Places application consists of two main components: a web service (web platform) and the smartphone application (app) and is enabled to be used anywhere in the world.It allows researchers to collect evidence base and demonstrate the social values of public spaces – backed by users’ opinion and views. Also, by providing evidence and demonstrating that public space is having a positive societal impact can increase the enthusiasm for more inclusive and responsive public spaces.

By collecting such data, the C3Places App contributes to better explore and more precisely research on public space practices, as well integrate the use and point of view of several users on different spaces. Another interesting feature lies in the possibility to collect the weather conditions automatically, therefore researchers can also reflect on how weather conditions affect (or not) the usage of public open spaces.

Finally, considering that it is up to the researcher to create the questions or the photo questionnaire, the possibilities are infinite and can be addressed directly to each research topic that is being carried out. So, the C3Places app allows scholars and researchers to make more specific or broader public open space research and, since it runs in Android operative system, the range is quite extensive. The use of the C3Places App is free and can be requested at c3places.coordination@ulusofona.pt.

The manual for preparing a research subject with the help of the C3Places App can be downloaded here.

Reflections on teenagers use of public open space

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

C3Places Lisbon reflected on teenagers use and needs on public open space. Space observations evidenced the strong role of public spaces in Alvalade but, in broad terms, revealed that teenager’s usage turned out much lower than supposed. This was confirmed also by the difficulty identifying public spaces in the neighbourhood in the living labs. In the school surroundings, teenagers’ use of public space is directly related with school activities and schedules. Students using the space, mostly are in groups, talking, hanging out or smoking. Due to a lack of sitting equipment in the area, the students use the bus stop shelter (where there is the only bench available), or sit in different places with other functions (at a bikes station, café tables, on the floor, on walls and access ramps, or on the steps of the building entrances), what can cause conflict among teenagers and with other users. However, it seems clear that the majority of students also only cross this space (figure 1).

Experts from the parish council see teenagers as a difficult group to work for/with since they mostly assume that teenagers’ behaviour in public spaces is inadequate and damaging to the space and its equipment. Nevertheless, they are aware that adolescence is a period of transition and acknowledge that there is a lack of public spaces that meet teenagers’ needs. Experts expect that the creation of flexible and multipurpose places, suiting different users, can diminish potential conflicts. Regarding the involvement of teenagers, a collaboration with schools is perceived as beneficial to engage teenagers in public discussions, from where they are currently absent from.

The teenagers engaged in co-creation, had a weak urban literacy, what made it difficult at times to reflect on their use of public space. Their favourite places also seem to be private and indoor spaces, such as shopping malls, where they hang out and meet peers. However, the labs boost discussion on public space and main conclusion seems to point to a lack of public spaces meeting teenagers’ needs, in Alvaalde neighbourhood. Teenagers’ want quality public spaces, diverse and well equipped, easily accessible (by private and public transportation) and where they can meet and hang out with friends, sit in groups and feel welcome. In the second phase of living labs two groups propose ideas for transformation of a public space in front of the school, used by students. The first group proposes a public meeting place for social gathering, with benches and tables with trees casting shadows, and changes in the street structure to increase pedestrian safety (more crossing, street narrowing). The second group proposed a new street design with less parking slots to create shared spaces and therefore increase road safety. The group suggested a green space with kiosk, trees, circular wooden benches and enhanced with a wi-fi hotspot and water dispenser.