For inclusive communities the involvement of all relevant stakeholders is essential. Involving the community means building relationships.

The community is at the core of placemaking, the process of involving people to “collectively reimagine and reinvent public spaces” (PPS) and its engagement should result in integrated knowledge and be translated in actions towards more inclusive and responsive public spaces.

For practice this also means advancing the co-creation of knowledge, collaborative agenda-setting and joint decision on commitments.

Community involvement combines therefore elements of interactive engagement and intervention, provided that an active promotion of opportunities for participation is in place.

There are different ways of involving the community and for refining commitment, these goes from in-kind and financial support, volunteering, engaging in different tasks, contributing with opinion and local knowledge.

Enduring after all partnerships and through establishing and strengthening collaboration community involvement creates capacity to address changes in public policies.

Smart Co-design. An interdisciplinary approach to urban planning via Augmented/Virtual Reality and process mining

Authors: Barbara Piga, Marco Boffi, Nicola Rainisio, Gabriele Stancato, Paolo Ceravolo, Gabriel Marques Tavares

In the field of urban planning and design, citizens’ involvement has undergone a constant evolution. This has taken place in quantitative terms, with an increasing number of citizens involved in each urban transformation, together with a greater number of initiatives for collaborative approaches (Davies et al., 2012). Such evolution is also qualitative, as more attention is nowadays devoted to disadvantaged social minorities and citizens are more often considered as partners rather than passive observers (Bisschops & Beunen, 2019). In this context, the opportunities offered by ICT solutions have represented a natural field of expansion for these practices. This process has been further strengthened by the rapid and widespread diffusion of mobile devices, which allow building networks interconnecting different actors, at the same time and in different places, among them and with the city. Moreover, such interaction between urban planning and ICT has produced several innovations in terms of services offered to the citizens (Dunn, 2007; Piga et al., 2021).

Yet, the role of the social sciences has so far been partial in those initiatives, despite the proximity of some research issues. In particular, environmental and community psychology developed several theoretical concepts and measurement tools relevant for this field. Thanks to their implementation, the relationships of individuals within a community and with the physical environment in which they live can be effectively described. This union between the physical and intangible components of the places we live has rarely been effectively integrated into applied tools (Boffi & Rainisio, 2017). At the intersection of these different perspectives on experiential urban planning (Piga, 2017) lies the starting point of the collaboration between the Università degli Studi di Milano and the Politecnico di Milano.

It was further developed thanks to the “AR4CUP: Augmented Reality for Collaborative Urban Planning” projects (2019 and 2020), part of the H2020 EIT Digital (Digital Cities) funding program whose Italian partnership was led by the Politecnico di Milano. The objective of the project is to support the design of urban spaces, through an app (AR4CUP) that makes people’s urban experiences evident and quantifiable using synchronous behavioral data (Seeber, 2014).

In a nutshell, this smart co-design approach fosters the inclusion of the urban communities perspectives in the design process. Mixed Reality is exploited to combine real and virtual environments (Carmignani et al., 2011). The result is a combination of information coming directly from the real environment with information coming from design artifacts: data are collected recording the user response to this mixed reality in real-time. Indeed, the app has different functions that enable its application throughout an entire co-design process:

- it shows, on-site through Augmented Reality and off-site through Virtual Reality, urban and architectural proposals geolocated in real dimensions before their actual implementation; it also allows to explore the current condition of the neighborhood;

- it collects data from citizens’ reactions to proposed urban transformations or to the current environment, combining emotional, cognitive and behavioral factors through scientifically validated instruments;

- it develops automatic data analytics to study the user’s behavior, to verify its conformance with the design goals and to identify space utilization not explicitly considered by the design plans;

- it represents the outcomes in various forms, including charts and maps of the places as they are subjectively perceived.

The app and its outcomes are conceived as a tool for facilitating the interaction among stakeholders of urban transformations (e.g. Architectural Firms, Real Estate Developers), institutions (e.g. Local Public Administrators, Regional or National authorities) and citizens (e.g. dwellers, commuters, tourists). It eases the creation of a shared representation of places, combining together objective environmental features and subjectively perceived values. Such common ground is crucial for informing designers and decision-makers about citizens’ needs, which might impact on the project development. In addition, it is a way to effectively inform citizens and actively engage them in the urban transformation from the very beginning of the process.

References

- Bisschops, S., & Beunen, R. (2019). A new role for citizens’ initiatives: The difficulties in co-creating institutional change in urban planning. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(1), 72–87.

- Boffi, M., & Rainisio, N. (2017). To Be There, Or Not To Be. Designing Subjective Urban Experiences. In Urban Design and Representation (pp. 37-53). Springer, Cham.

- Carmigniani, J., Furht, B., Anisetti, M., Ceravolo, P., Damiani, E., & Ivkovic, M. (2011). Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimedia tools and applications, 51(1), 341-377.

- Davies, S. R., Selin, C., Gano, G., & Pereira, Â. G. (2012). Citizen engagement and urban change: Three case studies of material deliberation. Cities, 29(6), 351–357.

- Dunn, C. E. (2007). Participatory GIS — a people’s GIS? Progress in Human Geography, 31(5), 616–637.

- Piga, B. E. (2017). Experiential simulation for urban design: From design thinking to final presentation. In Urban Design and Representation (pp. 23-36). Springer, Cham.

- Van Der Aalst, W., Adriansyah, A., De Medeiros, A. K. A., Arcieri, F., Baier, T., Blickle, T., … & Burattin, A. (2011, August). Process mining manifesto. In International Conference on Business Process Management (pp. 169-194). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Co-creation of teenagers-sensitive public spaces

Authors: Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Joana Solipa Batista, Marluci Menezes

This paper explores the nexus public spaces – users and co-creation based on the research Project C3Places. The Project, using the potential of co-creation to inspire placemaking, aims to inform decision making to increase the attractiveness, responsiveness, and inclusiveness of public open spaces. It reflects on the results of a case study in Lisbon centered on teenagers as potential co-creators of public spaces, their spatial practices, along with perceptions, needs, and requirements. It also addresses the negotiation of public space by teenagers, the potential of living labs for placemaking and the analysis of local policies and strategies that support civic involvement. The living labs, a central part of this study, were completed prior to Spring 2020, so the research and insights do not reference the global public health crisis caused by COVID-19. This has changed our ordinary everyday life, and the major enduring effect is the way we are allowed to use and move through public spaces. However, when we all are suddenly forced to reconsider our relationship to public spaces, their potential to support a range of inclusiveness becomes even stronger.

Smaniotto Costa, C., Solipa Batista, J., Menezes, M. (2021). Co-Creation of Teenager-Sensitive Public Spaces. The C3Places Project Living Labs in Lisbon, Portugal. Focus, Journal of the City and Regional Planning Department, San Luis Obispo, Ca: Vol. 17: 52-62.

Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies

Author: Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Marluci Menezes

There is an increasing awareness and advocacy claim for engaging the society in the production of public open spaces. This contribution seeks to increase knowledge on the relationship between spaces and the social practices of teenagers, towards a more inclusive and interactive process of public space co-creation. It is based on two European Projects: CyberParks and C3Places, and explores teenagers’ spatial practice and needs, and how to engage them in the process of co-creating more sensitive public spaces, while exploring the challenges and opportunities ICT open. This paper, the results of a case study taking place in Lisbon and the analysis of questionnaires and interviews are discussed.

Smaniotto Costa, C., Solipa, J., Almeida, I., & Menezes, M. (2020). Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies. Cities, vol. 98. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.102574.

Social Campus

Author: R. Pizzi

The platform was created by the Department of Computer Science of the dell’Università degli Studi di Milano of the as part of the C3Places European Project, which aims to develop strategies and tools to increase the quality of open public spaces through the information and communication technologies. This platform aims to create a community of students, teachers and citizens who attend the Città Studi Campus and its open spaces.

On this web site you can ask, receive and yield information on the various places of interest scattered around the area simply by registering.

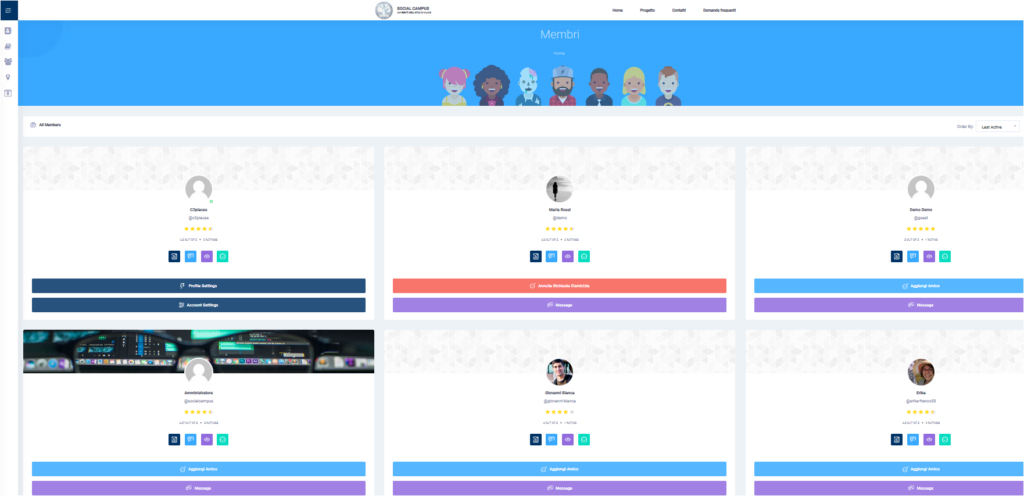

Entering the dedicated pages it will be possible to interact with the registered members that share the same interests. In the groups section you will be able to communicate with the registered members (Figure 1). The group page can also be reached by scanning the QR code on the plate affixed in proximity to the point of interest (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1: Social Campus view of the members page and of a chat between members.

Figure 3: Social Campus: an example of QR code tag.

The University of Milan contribution to the C3Places Project

Author: R. Pizzi

The presentation at the link describes the idea developed by the UNIMI team: a vibrant new way to create a community that could really communicate and help and grow not only virtually but also in presence *by means* of technology.

Urban open space can easily become center of shared services and cultural events and opportunities and knowledge (Figure 1).

The availability of public hot spots in public places can be seen as a social service, where digital infrastructures may become a way for the supply of public services, ideas, creativity, opportunities for co-creation and collective cultural and social interchange, promoting sustainability, responsibility and knowledge of nature, the city and citizenship in its cultural diversity.

University of Milan main task in C3Places project was the development of a co-creation platform providing a scientifically validated framework for citizens’ interaction in and with public spaces, leveraging on their diversity potential of co-creation.

A social network built around points of interest of public open spaces, where people can exchange usefule information, moods, requests, ideas.

A complete example has been developed and experiment, yield the novel digital tool to students of the Campus, open also to the citizens living in the area.

Figure 1: View of the “Città Studi” area.

Actors and their roles in the co-creation of Public Open Space

Authors: Barbara Goličnik Marušić, Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Vita Žlender

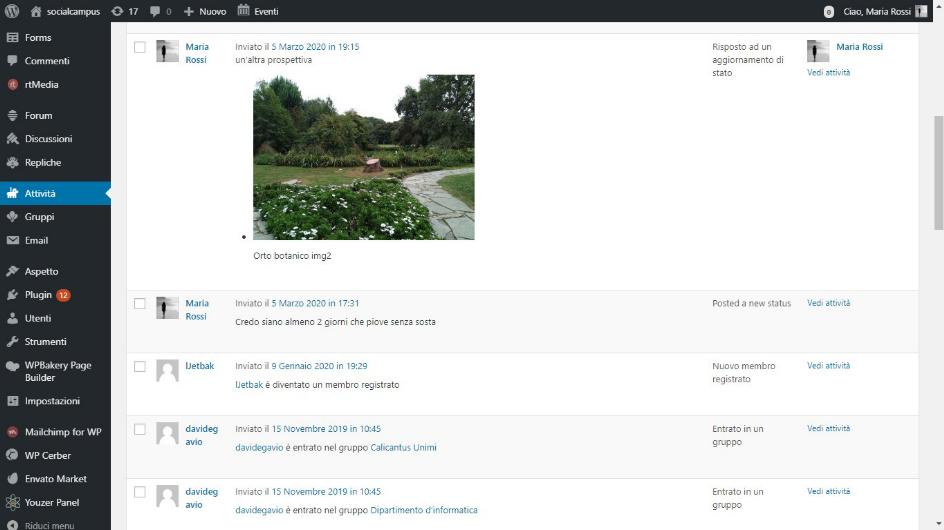

Despite the agreement in the academic literature that co-creation is a collective creative endeavour (Arnstein, 1969), we believe that the role of citizens and that of professionals differ.

With regard to the roles of citizens, Goličnik Marušić and Šuklje Erjavec (in press) elaborate on three diverse roles of the citizens as co-implementers, co-designers, and co-initiators, of which, only the co-initiator is highly involved in various steps of the contemporary planning process.

With regard to the roles of professionals, scholars use different terms to denote them, ranging from the role of initiator, metadesigner, negotiator, involver and enthusiast (see e.g. Eggertsen Teder, 2019; Vandael et al., 2018).

These roles might overlap with those identified in other literature as facilitator (e.g. Vandael et al., 2018) or a mediator (Goličnik Marušić & Šuklje Erjavec, in press). Different terms used might be a reason for the confusion and the uncomprehensive overview of roles.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the co-creation process needs structure and clearly defined roles, yet it should also remain open to individual suggestions and approaches to enhance the creativity of all parties involved and facilitate constructive problem solving.

We elaborated on the roles in Figure 2.

References:

- Žlender, V, Šuklje Erjavec, I & Goličnik Marušić, B (2020). Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process: Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice. Planning Practice and Research. DOI: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1829286.

- Goličnik Marušić, B., & Šuklje Erjavec, I. (2020) Understanding co-creation within urban open space development process, in: C. Smaniotto Costa, M. Mačiulienė, M. Menezes, & B. Goličnik Marušić. (Eds) Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice—Reflection—Learning. C3Places Project Lisbon: Lusófona University Press. ISBN 978-989-757-125-1. DOI https://doi.org/10.24140/2020-sct-vol.4-1.1.

Potentials and bottlenecks in digital co-creation with teenagers

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

C3Places Lisbon Living Lab allowed to reflect on the potential and bottlenecks in digital co-creation with teenagers. The labs revealed the importance, of clear messages, goals and expectations, shared from the beginning.

Such messages have to encompass what is going to happen, why is it happening, when each task has to be performed, which results are expected and what are the benefits for participants.

In Lisbon, the labs revealed teenagers’ have a weak urban literacy and low spatial representation skills, and difficulties in identifying own needs and expressing ideas for public spaces, but the theme sparks interest in most of them and the interactive activities provide a forum for learning about urban space and share experience of teenagers use of space and needs.

For this reason is important to assess the knowledge, abilities and motivations of the target participants, and harness their full potential to actively participate in co-creation of public open spaces. To assess the success rate and overall satisfaction with the labs, a short questionnaire was distributed at the end of the last session asking students to indicate the perceived learning effect. The results flutuate between a high satisfaction and a disatisfaction, in line with the general observation made during all sessions; while a group of students showed interest and conducted lively the discussion, another small group remained apart, even not reacting to a direct request to express their ideas or opinions.

While in the questions related to personal experience with collaboration and exchange of ideas, the agreement with statements was low, the ones related to learning effect by taking part of the workshops the agreement was higher.

This can be analysed as a positive benefit for increased knowledge gained by this type of participative methodology.

In this respect, it is noted that the living labs were inserted in the daily school activities, and the school board selected the classes that participated in the two phases.

The willingness and readiness to get involve in digital co-creation may be different than when students can choose on their own to participate.

The second phase of labs with teenagers tested the potential of using digital devices in co-creation of public open spaces. Tablets were provided for the participants and facilitators recommended the use of digital tools for collection and discussion of ideas and general group work.

The use of this devices may be benefitial to allow for more interactivity in co-creation. For digital co-creation, devices and tools should be provided and integrated in the proccess, efficiently and logically.

In Lisbon, results highlight a important role of digital co-creation to increase the awareness on placemaking and provide opportunities for teenagers (and other groups) to discuss different needs on public spaces. That discussion is a crucial one in urban planning, since public spaces are common goods and everyone should be able and encouraged to use them and share them with others.

Brief notes on user’s participation in public spaces planning and design

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

For C3Places a public space must be inclusive and responsive, allowing people to use it without restrictions and to fulfil socio-spatial needs. To achieve more inclusive and responsive spaces, users should have a voice in the process of planning and design, also known as placemaking (PPS, n. d.).

Engaging people actively calls for appropriate methodologies as inclusive design (Carmona, Heath, Tiesdell, & Oc, 2003) or co-creation, the last is at the core of C3Places research.

C3Places uses the terms inclusive and responsible place to describe a far-reaching framework of principles and best-practice on which communities can build a shared commitment to sustainability in social and urban development. For that, communities should be engaged in the making and transforming of public spaces from the very beginning.

Public space as a shared common good is the fundamental premise – public space is a resource which, if used responsibly, can help transform the way people live, work, recreate, and interact. In placemaking, stakeholders should have a clear understanding on how specific characteristics and shapes affect the experience of the space (Alves, 2005; Stevens, 2007).

Therefore, interested parties as different users’ groups, community facilitators, professionals, local authorities and municipalities, should be engaged directly, their opinions accounted for and their needs responded to by placemaking (Alves, 2005; Carmona et al., 2003; Thompson, 2002; UN-Habitat, 2015).

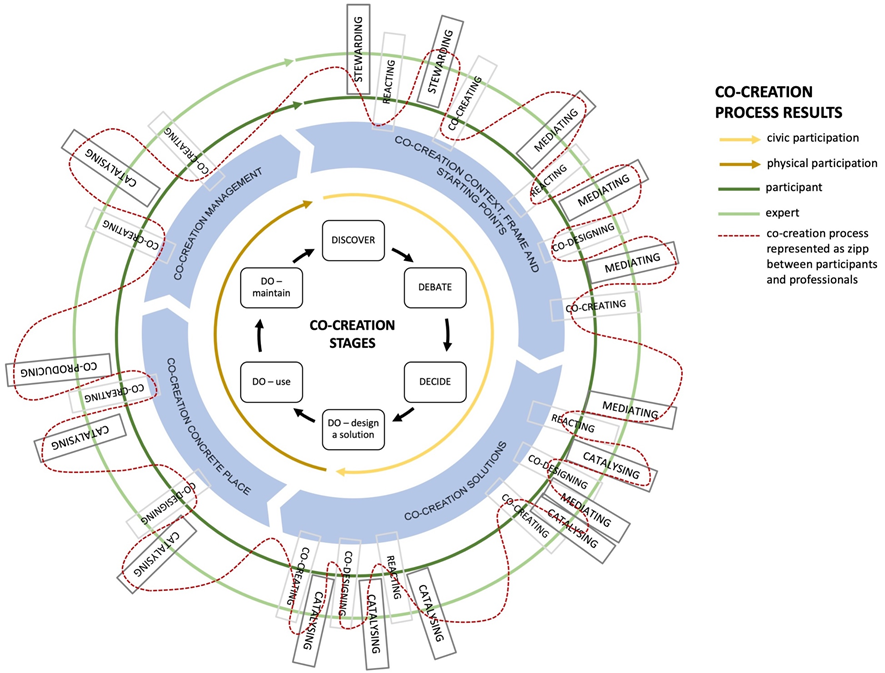

The case-study in Lisbon followed this recommendation and different stakeholders were brought together in the development and operationalisation of Living Labs (Figures 1 and 2) (Smaniotto-Costa, Almeida, Batista & Menezes, 2018).

Figure 1: Living Lab Lisbon – brainstorming exercise with participants to reflect on characteristics of and ideal public space. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2018)

Participative approaches bring challenges of different sorts: in terms of time to be invested, human resources, monitoring and structuring the process that may impose demands that are too high for planners and authorities to see the advantages; in deciding who to involve; the time offset between participation in the process and benefitting from the outcome may be too long for users to engage and, due to transitory needs of users’, too stretched to provide a response while the changes are still valid; questions may be considered too technical or complex for the comprehension of non-professionals and; participation may add a legitimacy to the process but without truly respecting the opinions and ideas of those involved (Alves, 2005; Jupp, 2007; Talen, 2000; Valentine, 2004).

Figure 2: Living Lab Lisbon – group work to draw ideas and proposals for transformation of a public open space. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2019)

However, creating collaborative environments for planning, designing and transforming public spaces is fundamental for a placemaking process more interactive and able to meet the needs of the community, and to produce public places that are more attractive, meaningful, inclusive and sustainable.

Co-creation, as an open process with no previous fixed results, is a challenge for all parts involved but it is at the same time an open door for innovative ideas and solutions. In co-creation a broader range of people come together around the same table to negotiate and reconcile their different needs and interests, solve problems, freely express their concerns and expectations and, ideally, foster a community around public spaces ensuring more sustainable use (Figure 3).

The experiences gained within C3Places in the Living labs in Ghent, Lisbon, Milan and Vilnius are described at the site MyC3Place.

Figure 3: Living Lab Lisbon – outdoor exercise for participants to observe and discover different public open spaces. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2018)

References:

- Alves, F. B. (2005). O Espaço Público Urbano. Qualidade, Avaliação e Participação Pública. Porto: Escola Superior Artística do Porto.

- Carmona, M., Heath, T., Tiesdell, S., & Oc, T. (2003). Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. Michigan: Architectural Press.

- Jupp, E. (2007). Participation, local knowledge and empowerment: Researching public space with young people. Environment and Planning A, 39(12), 2832–2844.

- PPS – Project for public spaces. (2017) The Placemaking Process.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Almeida, I., Batista, J., Menezes, M. (2018). Envolver adolescentes no pensar a cidade: reflexão sobre oficinas temáticas de urbanismo no Bairro de Alvalade, Lisboa. Engaging teenagers in placemaking: Reflections on thematic workshops in urban planning in Lisbon’s Alvalade Neighbourhood. Revista de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território (GOT), 15, 117-142, (in Portuguese).

- Stevens, Q. (2007). The Ludic City. London and New York: Routledge.

- Talen, E. (2000). The Problem with Community in Planning The Problem with Community, 15(2).

- Thompson, C. W. (2002). Urban open space in the 21st century. Landscape and Urban Planning, 60(2), 59–72.

- UN-Habitat. (2015). Adequate Open Public Space in Cities. A Human Settlements Indicator for Monitoring the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda.

- Valentine, G. (2004). Public space and the culture of childhood. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Loom of Ideas

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

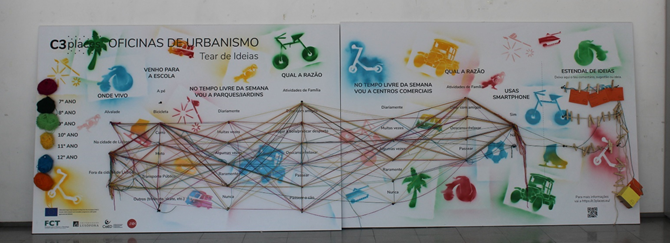

As a way to engage a higher number of students in a reflection on the use and quality of the space in front of the school, a visually attractive and interactive board – called Loom and Clothesline of Ideas (Figure 1).

The Loom was developed to encourage a broad participation of students identifying spatial qualities and problems and stands in the school hall from May to July 2019. It had seven multiple choice questions displayed in columns (place of living, mode of transportation from home to school, frequency of public open space use for leisure, the activities performed, use of commercial places in free time and reason for it and use of smartphone).

A nail indicated the place for each possible answer. For each school grade different coloured woollen yarns hanged next to the questions (the school has grade 7 to 12). To provide their answer the students should wrap the yarn around the corresponding nail (altogether 56 answers were collected) (Figure 2).

In the clothesline students could write down in cards comments, suggestions or ideas and hung them in the line (Figure 3).

Altogether 35 cards were collected. Two main issues raised from the cards: the request for more sitting facilities in the school yard and around the school, and the call for more outdoor activities.

Yet, placemaking can only make a direct contribution for the first issue, but on the flip side, when the outdoor conditions are more suitable, the second call – more outdoor activities – can be easier accomplished.

C3Places Lisbon

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

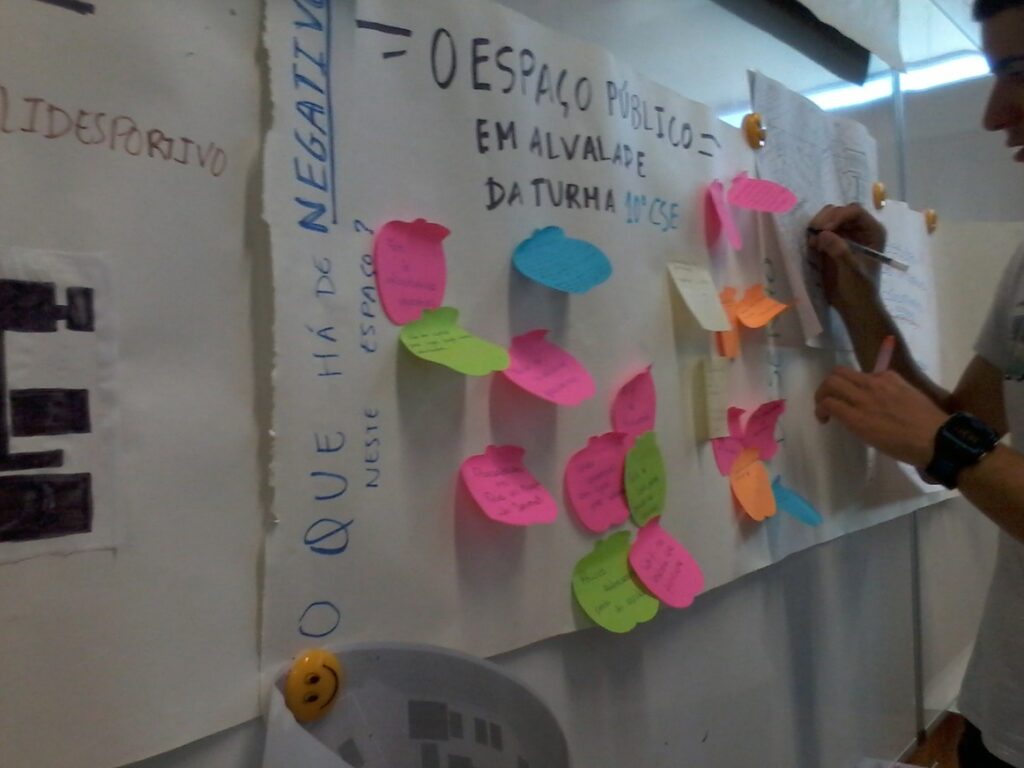

C3Places in Lisbon implemented living labs on urban planning and design targeting teenagers in Alvalade neighbourhood.

The labs were developed for co-creative and collaborative practice, exploring opportunities for a direct involvement of teenagers in placemaking, providing a platform for learning and free expression of values and ideas about and for urban fabric.

The methodology encompassed different tools, such as thematic workshops, exploratory site visits in the neighbourhood, discussions and debates sessions and questionnaires, focused on teenagers’ practices, uses and needs on public open spaces.

The living labs were implemented in two phases.

A pilot phase was organised between February and May 2018 with two 10th grade classes (N=49 students, aged 15 to 18), consisting in total of 24 hours intervention per class, with both indoor and outdoor activities, aimed at discussing the city and its production.

A methodological decision was made by the researchers on which data should be analysed in more depth. Materials as questionnaires and the facilitators observational notes, as direct tools for data collection, were prioritized. Questionnaires had closed questions, analysed quantitively, and open questions, analysed through thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Other data resulting from materials that provided support for the activities and exercises complemented and reinforced these analyses.

The second phase, a week-long lab was organised in May 2019 with two classes of the first year of professional training education (N=20, aged 16 to 18). The students developed and justified design proposals for the space in front of their school.

The labs were organised in four sessions of 1,5 hour each with an emphasis on group work and on the use of digital tools (Padlet, image bank, presentation programmes and Google Maps).

The facilitators observational notes, a questionnaire to assess importance of co-creation and the teenagers’ proposals presented by teenagers analysed. Living labs were complemented with other methods of data collection, as space observations and interviews with experts. Space observations enabled to obtain an overview of the whole neighbourhood, as well as a more focused outline on public spaces used by teenagers.

Two sets observations were conducted, undertaken at different periods of the day and different days of the week. Descriptive notes and an image library enriched the field work.

The first set of observations consisted of mapping out the local public spaces.

In the second set, the Marquês de Soveral Street, where the school is located, and well known and used space by the teenage students, was selected for detailed observations (during a twenty-day period).

Data were collected with the aid of two distinctive observation grids. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with the four planning experts working with public space issues at the Junta de Freguesia de Alvalade (parish council). The quality of the analysis is secured through several steps, such as: familiarization with the data; generating initial codes which were then aggregated into potential themes; initial themes review, and identifying final themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

References: