It is also the aim of C3Places to bring together knowledge about the way the community uses and appropriates the public space, in light of the new technologies towards creating new understandings of the relationships between spaces and social behaviour.

Users of public space may differ in a multitude of factors, such as predominant age, gender, religion, nationality and language, physical and mental abilities, standard of living, level of education, ‘majority’ or to a marginalised segment of the population.

This diversity must be considered when improving the quality of public open spaces and defining participatory dynamics. C3Places is concerned with theoretical and methodological approaches, as well as novel research findings to deliver answers to relevant questions such: What do people want from public space? Does this differ by socioeconomic status, gender, age? Menezes & Smaniotto (2017) addresses the questions research should pose in order to get a comprehensive picture of who uses public space, what for, when and with which artefacts.

These aspects are also relevant to better understand the way people use a public space and the resulting spatial practices. These combine therefore elements of sociology (people) and (urban) planning sciences (spaces) to examine the social and material constitution of spaces and the interactions between people and people, and people with their environment. C3Places is interested in the material and conceptual opportunities that socio-spatial practice affords, in order to be able to obtain more knowledge to guide the design of policies. The Project is therefore not interested in individual data but grouped phenomena on the basis of similarities.

The socio-spatial practices that build the C3Places knowledge base in Ghent, Lisbon, Milan and Vilnius are addressed at description of cases.

How ICT provision can improve aspects of spatial use and quality?

Authors: Ina Šuklje Erjavec

To better understand and present the complexity of the relationship between users’ needs for space use and quality and the necessary attributes and ways of using ICT tools to improve various aspects of space quality, we have prepared an overview table that includes and shortly describes key spatial quality aspects of the outdoor setting, list of some user needs related to both spatial and ICT use, ICT attributes relevant to fulfil those needs, some possibilities and types of ICT implementation, and suggestions of related added values to listed spatial quality aspects.

Legend:

- AR = Augmented Reality

- LT = Location Technology

- W = Wi-Fi

- VT = Vision Technology

- DM+ = Data Management plus more

| SPATIAL QUALITY ASPECTS | USER NEEDS | DIGITAL TOOLS /ICT | DIGITAL TOOLS /ICT | ADDED VALUES |

| Attributes | Type of implementation | |||

| (Public) Accessibility | Physical accessibility orientation, navigation, access for all (inclusiveness) Accessibility to technology – skills/use, affordability, equality (inclusiveness) | Easy to use (intuitive) devices, (no need to be ICT-literate) Path quality – access for all Online information before visiting place – available for all needs | Wayfinding apps – “filtering’ based on user profile and requirements Overlaying of additional information within App for specific purposes (augmented reality); In-situ devices LT, AR | • Enhancing access for all (facilitating it) • Responding more specifically to user requirements, • Possibility for user feedback to enrich data |

| Security | To feel safe in the space, not to be controlled or observed; to retain: – physical safety – emotional/ – psychological safety Internet security – not to be hacked | Physical and virtual privacy, confidence, alert to danger, feedback, security check | ICT tools and apps for: – Lighting – Sound and light interactivity – Suitable structure of place, good visibility, – Validated networks Monitoring cameras AR, LT, VT, W, DM | • Social networking • User’s involvement • New users • Higher usability • New ways of lighting • Flexibility • Activation system |

| Legibility | To understand the place/move easily | Readability | Planning – Layout and way-marking AR, LT, VT, W, DM | Better orientation flow of movement |

| Clear Identity of place | Unique features | Artworks, landscaping, facilities | Recognition, significance | |

| Sociability | Participation and inclusion Interaction | Gathering / social settings Interactive settings Play features | Clear space/ICT demarcation /time- independent but spatially localised social interaction AR, W, DM, LT | Well-being and social cohesion, ownership/care sense of belonging, e-agora |

| Adaptability | Adapt to special needs Co-create – temporarily change Capacity for individual change | Future-proof design Flexibility Ephemerality | Apps, Wi-Fi Sensors, Screens and other in-situ devices and settings (Regular maintenance and updating needed) VT, DM, W | Co-creation, citizen input, experimentation of solutions, possibly temporary |

| Functionality | Accessibility Comfort | Welcoming spaces, clear pathways | Social design and facility provision DM, LT | System trust |

| Connectability | Between spaces (permeability), people and information | Secure and high-bandwidth provision | Maintaining networks, facilitation W, DM | Social cohesion, communication |

| Variety | Attractors Opportunity of choice | Gaming, social, information layers | Embedded games and play, socially hybrid spaces – e.g. chess/coffee AR, LT, VT, W, DM | • Enjoyment • Play • New uses • Innovation |

| (Social) resilience in the face of emergency | Obtain and give effective and reliable information; Knowledge as to where to go; Access to amenities Organisational support for groups | Quick responsiveness Spatial adaptability to user needs ICT-functioning support Accessibility (to both space and technology) | Energy independence or passive energy generation Monitoring devices e.g. air/water quality, waste… W, DM, VT, LT | • Timely information provision and exchange • A direct communication channel e.g. via social media • Monitoring available resources |

| Environmental / ecological sustainability | Optimal microclimate Water retention Biodiversity Pollution and natural disaster mitigation | Real-time monitoring via sensors Visualising the information in situ | Sensors Screens Apps DM, VT, LT, in situ sensors | • Raising awareness and knowledge • Support policymaking and management |

| Health (physical and mental) and wellbeing | Outdoor physical activity Mental restoration (connection with nature) Knowledge about optimal environmental conditions to carry out physical activity | Challenging and attractive environment for physical activities; Virtual environment to enhance wellbeing; Real-time information; Health-related statistics | Innovative elements that invite one to perform physical activities Screens, Apps Games AR, VT, LT, DM | • Raising awareness, knowledge, promotion of a healthy lifestyle; • Attract new people outdoors; Incentivise activity of visitors; • Offer new experiences |

References:

- Šuklje Erjavec, I. & Žlender, V. (2020). Categorization of digital tools for co-creation of public open spaces. Key aspects and possibilities. Planning Practice and Research (165-183). In Smaniotto Costa, C., Mačiulienė, M., Menezes, M. & Goličnik Marušić, B. (Eds.). Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice – Reflection – Learning. C3Places Project. Lisbon: Lusófona University Press. https://doi.org/10.24140/2020-sct-vol.4-2.1.

- Šuklje Erjavec, Ina, and Ruchinskaya, Tatiana (2019). A Spotlight of Co-Creation and Inclusiveness of Public Open Spaces. In CyberParks – The Interface Between People, Places and Technology, edited by Smaniotto Costa C. et al. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11380. Springer, Cham.

- CyberParks Project. Pool of Examples (n.d.). Retrieved June 7, 2019. Available at http://cyberparks-project.eu/examples

Evaluation of digital tools for co-creation of public open space

Authors: Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Vita Žlender

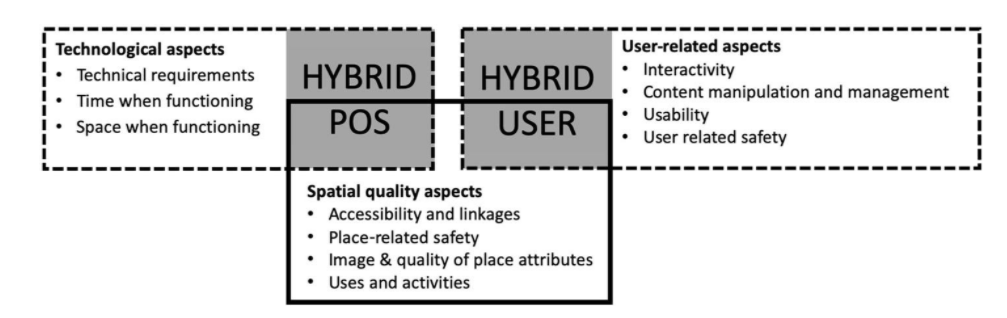

In relation to the Digital Co-Creation Index – a tool to assess, measure and compare digital co-creation initiatives, a conceptual framework was elaborated to convey the penetration of ICT into public spaces. The criteria are structured according to three aspects: spatial quality aspects, user-related aspects, and technological aspects (Figure 1).

SPATIAL QUALITY ASPECTS

The approach to evaluating these aspects is grounded on basic principles of researching, understanding and designing public spaces developed by theorists and practitioners such as W.H. Whyte, J. Gehl, S. Carr and others. Specifically, the criteria, indicators and tools from the Project for Public Spaces “The Place Diagram” (Project for Public Spaces, 2009) and Jan Gehl’s “12 Urban Quality Criteria” (2017) were examined more profoundly.

SPATIAL QUALITY ASPECTS

The approach to evaluating these aspects is grounded on basic principles of researching, understanding and designing public spaces developed by theorists and practitioners such as W.H. Whyte, J. Gehl, S. Carr and others. Specifically, the criteria, indicators and tools from the Project for Public Spaces “The Place Diagram” (Project for Public Spaces, 2009) and Jan Gehl’s “12 Urban Quality Criteria” (2017) were examined more profoundly. In addition, we took into consideration the outcomes of the CyberParks Project and evaluated the performance of the C3Places POS Quality Index (C3Places, 2019) for the Living Labs assessment that we adapted to the current context of POS, with its digital transformation in mind. The main spatial quality aspects which include additional dimensions relevant for ICT penetration into POS, are defined as:

- Accessibility and linkages – Legibility, Navigation, Convenience for movement, Interlinking, Level of physical, social and digital accessibility.

- Place-related safety – Vandalism, Traffic, Injuries, Environmental safety (monitoring).

- Image & Quality of place attributes – Attractiveness, Personalisation and individual creation possibilities, Adaptability, Monitoring, Environmental quality and Ecological sustainability.

- Uses and activities – Communication and education possibilities, Access to information, Sociability, Research possibilities, Playfulness, Variety, Responsiveness, Service provision, Health and wellbeing.

USER-RELATED ASPECTS

To define criteria for these aspects, our guiding question was: Which characteristics of ICT are needed to satisfy use and successful co-creation experiences? As basis for development of criteria the Social Responsiveness Index and the Digital Inclusiveness Index were used, plus a sub-indices of Digital Co-Creation Index (C3Places, 2019) and literature review of existing classifications and criteria of ICT features to enable satisfactory user experience. We considered criteria for methods and approaches selection from “Participedia” (n.d.) and the work of Kaplan & Haenlein (2014), who focused on collaborative projects, such as one on ICT tools, grouping them along two dimensions: type of knowledge that is created within a collaborative project, and mutual independence of individual contributions. We define user related aspects as:

- Interactivity – User’s engagement along with the device/ media/ application used, its type of interaction, degree of interaction and type of experience

- Content manipulation and management – How is it provided and what is user supply?

- Usability – Ease of use, respect for privacy, saving work for future use, customization potential, possibility of choice

- User-related safety – security and privacy assurance technology (protection of personal data, anonymity of ideas, etc.) and social resilience

TECHNOLOGICAL ASPECTS

The guiding question for the technological aspects was: How can digital technology support quality of place and the way the place is used and developed? The main issues to define are:

- Technical requirements regarding software, hardware and network communication, and their installation: is there a need for the internet, are any specific operational systems required, i.e. electricity, speakers, etc.?

- From the time-related point of view: is the ICT tool functioning permanently or temporarily, continuously or intermittently?

- From the point of view of functioning place: is the ICT tool static, located in the POS, portable, to be used in POS, or remotely accessible to be used for distant POS-related activities?

On this basis, we have systemised types of ICT tools and their supporting devices in three main categories which describe where the tool is installed in relation to the open space and how an ICT tool interacts with the user. The subtypes of tools are defined according to POS, user-related functions and specific characteristics. Thus, the developed framework for classifying digital tools for co-creation is addressed in the next section.

References:

- Šuklje Erjavec, I. & Žlender, V. (2020). Categorization of digital tools for co-creation of public open spaces. Key aspects and possibilities. Planning Practice and Research (165-183). In Smaniotto Costa, C., Mačiulienė, M., Menezes, M. & Goličnik Marušić, B. (Eds.). Co-Creation of Public Open Places. Practice – Reflection – Learning. C3Places Project. Lisbon: Lusófona University Press. https://doi.org/10.24140/2020-sct-vol.4-2.1.

- C3Places. (2019). Methodological Framework for LIVING LABS in European Cities. Available athttps://c3places.eu/outcomes.

- Gehl, J. (2017). Twelve Urban Quality Criteria. Available at https://gehlinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/TWELVE-QUALITY-CRITERIA.pdf

- Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2014). Collaborative projects (social media application): About Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Business Horizons, 57(5), 617–626. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.05.004.

- Participedia. (n.d.). Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- PPS – Project for Public Spaces. (2009). What Makes a Successful Place? Retrieved 10 June 2019. Available at https://www.pps.org/article/grplacefeat.

Possible benefits of using ICT tools in co-creation process

Authors: Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Vita Žlender

To effectively use all the ICT potential it is important to understand co-creation in its broader sense: as a process that includes all stages of POS development and addresses all types of related collaboration activities, such as involving end users (citizens) and other relevant stakeholders, sharing information and local knowledge, collaborating on data gathering, expressing opinions, needs, wishes and values, defining priorities, visions and aims, working on decision making as well as placemaking with different participatory planning and co-design activities and comanagement (Šuklje Erjavec, 2017; Šuklje Erjavec & Ruchinskaya, 2019).

As further next step towards better understanding the possibilities for co-creation, we developed the following structure of the possible use of different ICT tools. It explains the type of function and way of integration in the process of planning and design, place making, place management and community engagement.

FOR EXPERTISE WORK – technology for supporting spatial development processes

>in the process of spatial planning and design, digital tools could be used to better:

- Understand, analyse and evaluate spatial and social state of the art faster, more deeply and comprehensively

- Assess and evaluate proposals more transparently

- Develop more transparent solutions, scenarios and models

- Present solutions more understandably and efficiently for non-experts (hardware and software)

- Perform sharing, co-production, co-creating, co-designing between experts and with stakeholders

FOR PLACE FUNCTIONING – technology in place & technology supporting the use of place

>in the process of place making, digital tools could increase:

- Responsiveness and adaptability of place

- Communication about place and within place

- Orientation and access to information

- Attractiveness, usability and playfulness of place

- Identity and recognizability of place

- Personalization and individual creation possibilities

- Education possibilities

- Research possibilities, etc.

>in the process of place management, digital tools could increase

- Monitoring – environmental and spatial quality

- Maintenance feedback (sensors, mobile apps, platform)

- Work coordination

- Traffic management

- Cultural content management

- Technical management

- Maintenance management

- Information management, etc.

FOR COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT – technology for supporting community engagement

>to raise awareness and increase involvement of the community, digital tools could increase the effectiveness of:

- Information collection, sharing and management

- Social communication, interactivity and networking management

- Public involvement and participation

- Co-creation process management

- Construction of community capacity and common issues and goals

Reference:

Methodological Framework for Living Labs for co-creation of public spaces

The methodology proposed for the Project C3Places covers the coordinated implementation of the case studies – each one devoted to different user groups and different types of public spaces – enabling C3Places to reach a wide range of users and urban spaces typology. The case areas identified will give an overview of state-of-art in the interaction between people – places and technology, and will serve as living lab for exploiting new approaches. The Methodological Framework for living labs in European Cities sets the guidelines for application of C3Places framework in 4 national living labs and supports their coordination.

The cases of living labs address communities’ or government initiatives, stakeholders, existing and new ICT-based applications from local and global industrial companies. The data and information collected on selected public open spaces in Belgium, Italy, Lithuania and Portugal enable C3Places to analyse and compare expectations, behaviours and attitudes of different user groups.

The proposed methodology is mainly concerned with assessing and monitoring the impacts and processes before, during, and after the implementation of cases where co-creation plays a vital role. The Methodological Framework consists of the Methodology for Exploring living labs, the Template of living lab Work Plan and the Template of living lab Report.

Through the proposed framework several aspects relevant to assessment and understating of co-creation processes (e.g. collection of data, generalization of gathered data in living lab studies) will be tested and evaluated against the comparability levels.

Co-creation of public open places. Practice – Reflection – Learning

In 17 chapters different invited authors share their experiences in actively involving stakeholders in the production and consumption of public open spaces. With these chapters the Project sparks the discussion on the co-creation for more sustainable, inclusive, attractive and responsive public open spaces. It intends to help researchers, governments and drivers in understanding and implementing more collaborative actions.

The authors share experiences, visions and reflections on how co-creation and participatory processes can open up possibilities for a sustainable and equitable future. This book emphasises three dimensions: practice, reflection, and learning. Practice concerns driving actions, identified and analysed experiences that serve as key models. Reflection refers to exploring and examining the results and performances of a co-creation process. Learning approaches the knowledge transfer and replication induced by the synergy of the different actors involved in this book.

Smart Co-design. An interdisciplinary approach to urban planning via Augmented/Virtual Reality and process mining

Authors: Barbara Piga, Marco Boffi, Nicola Rainisio, Gabriele Stancato, Paolo Ceravolo, Gabriel Marques Tavares

In the field of urban planning and design, citizens’ involvement has undergone a constant evolution. This has taken place in quantitative terms, with an increasing number of citizens involved in each urban transformation, together with a greater number of initiatives for collaborative approaches (Davies et al., 2012). Such evolution is also qualitative, as more attention is nowadays devoted to disadvantaged social minorities and citizens are more often considered as partners rather than passive observers (Bisschops & Beunen, 2019). In this context, the opportunities offered by ICT solutions have represented a natural field of expansion for these practices. This process has been further strengthened by the rapid and widespread diffusion of mobile devices, which allow building networks interconnecting different actors, at the same time and in different places, among them and with the city. Moreover, such interaction between urban planning and ICT has produced several innovations in terms of services offered to the citizens (Dunn, 2007; Piga et al., 2021).

Yet, the role of the social sciences has so far been partial in those initiatives, despite the proximity of some research issues. In particular, environmental and community psychology developed several theoretical concepts and measurement tools relevant for this field. Thanks to their implementation, the relationships of individuals within a community and with the physical environment in which they live can be effectively described. This union between the physical and intangible components of the places we live has rarely been effectively integrated into applied tools (Boffi & Rainisio, 2017). At the intersection of these different perspectives on experiential urban planning (Piga, 2017) lies the starting point of the collaboration between the Università degli Studi di Milano and the Politecnico di Milano.

It was further developed thanks to the “AR4CUP: Augmented Reality for Collaborative Urban Planning” projects (2019 and 2020), part of the H2020 EIT Digital (Digital Cities) funding program whose Italian partnership was led by the Politecnico di Milano. The objective of the project is to support the design of urban spaces, through an app (AR4CUP) that makes people’s urban experiences evident and quantifiable using synchronous behavioral data (Seeber, 2014).

In a nutshell, this smart co-design approach fosters the inclusion of the urban communities perspectives in the design process. Mixed Reality is exploited to combine real and virtual environments (Carmignani et al., 2011). The result is a combination of information coming directly from the real environment with information coming from design artifacts: data are collected recording the user response to this mixed reality in real-time. Indeed, the app has different functions that enable its application throughout an entire co-design process:

- it shows, on-site through Augmented Reality and off-site through Virtual Reality, urban and architectural proposals geolocated in real dimensions before their actual implementation; it also allows to explore the current condition of the neighborhood;

- it collects data from citizens’ reactions to proposed urban transformations or to the current environment, combining emotional, cognitive and behavioral factors through scientifically validated instruments;

- it develops automatic data analytics to study the user’s behavior, to verify its conformance with the design goals and to identify space utilization not explicitly considered by the design plans;

- it represents the outcomes in various forms, including charts and maps of the places as they are subjectively perceived.

The app and its outcomes are conceived as a tool for facilitating the interaction among stakeholders of urban transformations (e.g. Architectural Firms, Real Estate Developers), institutions (e.g. Local Public Administrators, Regional or National authorities) and citizens (e.g. dwellers, commuters, tourists). It eases the creation of a shared representation of places, combining together objective environmental features and subjectively perceived values. Such common ground is crucial for informing designers and decision-makers about citizens’ needs, which might impact on the project development. In addition, it is a way to effectively inform citizens and actively engage them in the urban transformation from the very beginning of the process.

References

- Bisschops, S., & Beunen, R. (2019). A new role for citizens’ initiatives: The difficulties in co-creating institutional change in urban planning. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(1), 72–87.

- Boffi, M., & Rainisio, N. (2017). To Be There, Or Not To Be. Designing Subjective Urban Experiences. In Urban Design and Representation (pp. 37-53). Springer, Cham.

- Carmigniani, J., Furht, B., Anisetti, M., Ceravolo, P., Damiani, E., & Ivkovic, M. (2011). Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimedia tools and applications, 51(1), 341-377.

- Davies, S. R., Selin, C., Gano, G., & Pereira, Â. G. (2012). Citizen engagement and urban change: Three case studies of material deliberation. Cities, 29(6), 351–357.

- Dunn, C. E. (2007). Participatory GIS — a people’s GIS? Progress in Human Geography, 31(5), 616–637.

- Piga, B. E. (2017). Experiential simulation for urban design: From design thinking to final presentation. In Urban Design and Representation (pp. 23-36). Springer, Cham.

- Van Der Aalst, W., Adriansyah, A., De Medeiros, A. K. A., Arcieri, F., Baier, T., Blickle, T., … & Burattin, A. (2011, August). Process mining manifesto. In International Conference on Business Process Management (pp. 169-194). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Co-creation of teenagers-sensitive public spaces

Authors: Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Joana Solipa Batista, Marluci Menezes

This paper explores the nexus public spaces – users and co-creation based on the research Project C3Places. The Project, using the potential of co-creation to inspire placemaking, aims to inform decision making to increase the attractiveness, responsiveness, and inclusiveness of public open spaces. It reflects on the results of a case study in Lisbon centered on teenagers as potential co-creators of public spaces, their spatial practices, along with perceptions, needs, and requirements. It also addresses the negotiation of public space by teenagers, the potential of living labs for placemaking and the analysis of local policies and strategies that support civic involvement. The living labs, a central part of this study, were completed prior to Spring 2020, so the research and insights do not reference the global public health crisis caused by COVID-19. This has changed our ordinary everyday life, and the major enduring effect is the way we are allowed to use and move through public spaces. However, when we all are suddenly forced to reconsider our relationship to public spaces, their potential to support a range of inclusiveness becomes even stronger.

Smaniotto Costa, C., Solipa Batista, J., Menezes, M. (2021). Co-Creation of Teenager-Sensitive Public Spaces. The C3Places Project Living Labs in Lisbon, Portugal. Focus, Journal of the City and Regional Planning Department, San Luis Obispo, Ca: Vol. 17: 52-62.

Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies

Author: Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Marluci Menezes

There is an increasing awareness and advocacy claim for engaging the society in the production of public open spaces. This contribution seeks to increase knowledge on the relationship between spaces and the social practices of teenagers, towards a more inclusive and interactive process of public space co-creation. It is based on two European Projects: CyberParks and C3Places, and explores teenagers’ spatial practice and needs, and how to engage them in the process of co-creating more sensitive public spaces, while exploring the challenges and opportunities ICT open. This paper, the results of a case study taking place in Lisbon and the analysis of questionnaires and interviews are discussed.

Smaniotto Costa, C., Solipa, J., Almeida, I., & Menezes, M. (2020). Exploring teenagers’ spatial practices and needs in light of new communication technologies. Cities, vol. 98. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.102574.

An example of digitally shared infrastructure creating a partecipatory community in an urban open spaces

Author: R. Pizzi

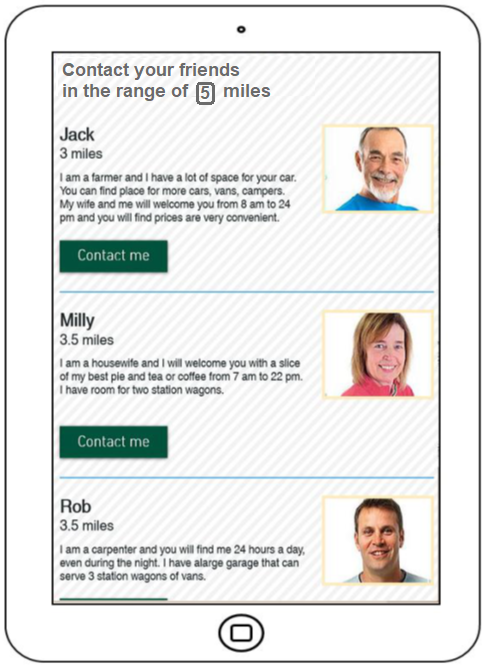

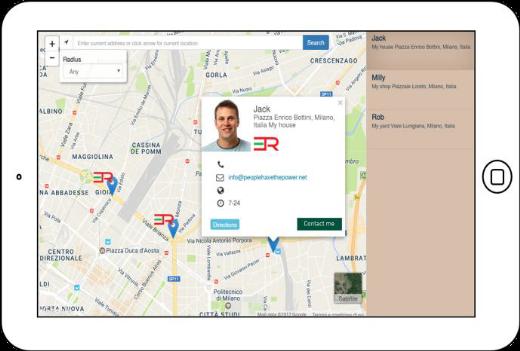

An open project of the Department of Computer Science of the University of Milan, PEOPLE HAVE THE POWER , in collaboration with the Polytechnic University of Milan (Department of Architecture, Construction Engineering and Built Environment) has proposed a geolocalized app that allows to find in the vicinity of your vehicle private buildings available to lend an electric outlet for charging electric vehicles, especially in yards, garages or parking spots.

As shown in the dedicated platform, the app allows individuals, companies or commercial activities to register, describe their service, arrange payment via PayPal or credit card, or promote their charging spots with scores collection and exchange, discounts etc.

Users can use the recharge service while leaving the vehicle for commissions or for leisure, or during a holiday trip or when stopping for the night.

The project was developed and a charging point was realized in the “Study City” Campus and has become a point of interest of the Social Campus platform (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4)

Figure 1: Social Campus: the QR code tag of the Smart charging point for soft electric vehicles.

Figure 2: The Smart charging point, inserted in the facade of the building.

Figure 3: Smart charging point position.

Figure 4: Smart charging point close-up view.

Social Campus

Author: R. Pizzi

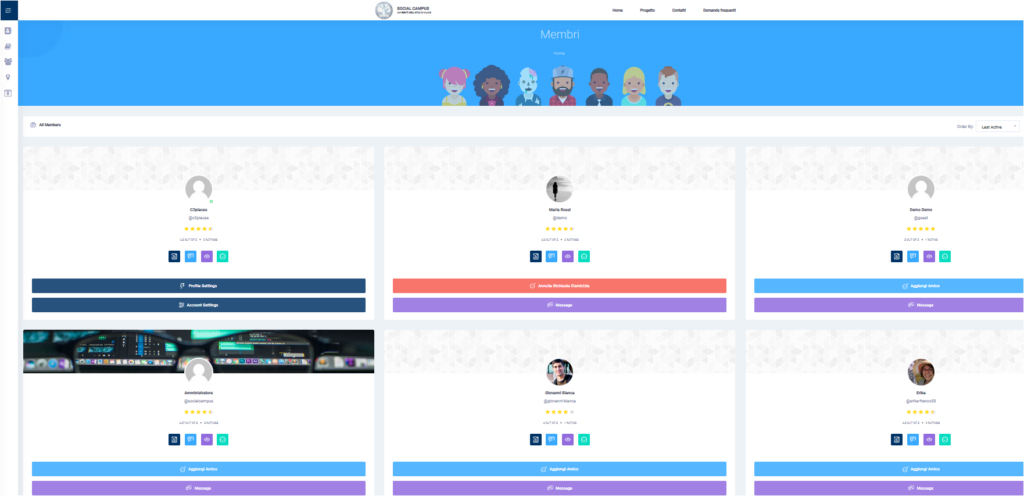

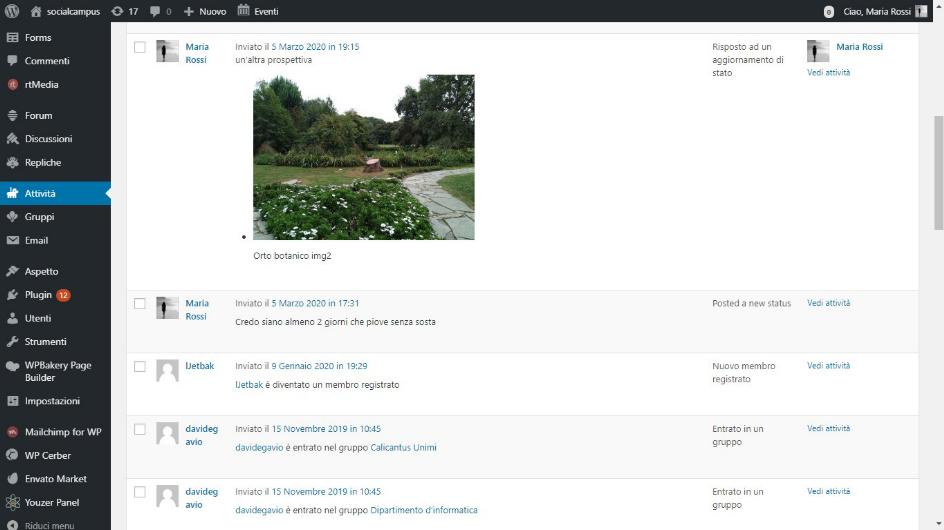

The platform was created by the Department of Computer Science of the dell’Università degli Studi di Milano of the as part of the C3Places European Project, which aims to develop strategies and tools to increase the quality of open public spaces through the information and communication technologies. This platform aims to create a community of students, teachers and citizens who attend the Città Studi Campus and its open spaces.

On this web site you can ask, receive and yield information on the various places of interest scattered around the area simply by registering.

Entering the dedicated pages it will be possible to interact with the registered members that share the same interests. In the groups section you will be able to communicate with the registered members (Figure 1). The group page can also be reached by scanning the QR code on the plate affixed in proximity to the point of interest (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1: Social Campus view of the members page and of a chat between members.

Figure 3: Social Campus: an example of QR code tag.

The University of Milan contribution to the C3Places Project

Author: R. Pizzi

The presentation at the link describes the idea developed by the UNIMI team: a vibrant new way to create a community that could really communicate and help and grow not only virtually but also in presence *by means* of technology.

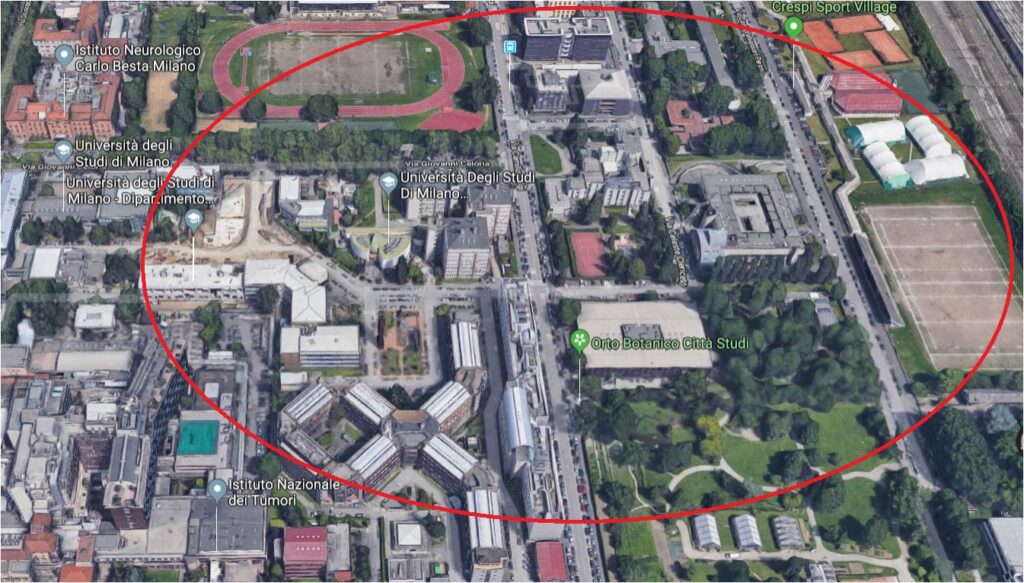

Urban open space can easily become center of shared services and cultural events and opportunities and knowledge (Figure 1).

The availability of public hot spots in public places can be seen as a social service, where digital infrastructures may become a way for the supply of public services, ideas, creativity, opportunities for co-creation and collective cultural and social interchange, promoting sustainability, responsibility and knowledge of nature, the city and citizenship in its cultural diversity.

University of Milan main task in C3Places project was the development of a co-creation platform providing a scientifically validated framework for citizens’ interaction in and with public spaces, leveraging on their diversity potential of co-creation.

A social network built around points of interest of public open spaces, where people can exchange usefule information, moods, requests, ideas.

A complete example has been developed and experiment, yield the novel digital tool to students of the Campus, open also to the citizens living in the area.

Figure 1: View of the “Città Studi” area.

Participatory co-creation and urban sustainability: the role of cooperation in the ICT era

Authors: R. Pizzi, A. Merletti De Palo

In the last decade Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) have become an important tool for socialization. However, living public open spaces firsthand remains fundamental for the development of the cultural identity of a community. ICT allows to develop strategies and tools to increase the quality of public open spaces, positively influencing the co-participatory creation and the effects of social cohesion (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The university area “Città Studi” where the Social Campus points of interest are located.

As part of a European research project called C3Places, we intend to generate knowledge and knowhow for a co-creation approach to be used to combine the use of ICT and the studies on cooperation with the essential functions and new potential of the public open spaces (Figures 2 and 3).

We explored the new dynamics of the open spaces as a value-added service for the community, paying attention to the parties interested, to the local context and to the different social groups.

Figure 2: App interface: services and contacts of the private charging points.

Figure 3: The private charging points are geolocalized.

Co-Creazione partecipativa e Sostenibilità Urbana: il Ruolo della Cooperazione nell’Era dell’ICT 2018 / R. Pizzi, A. Merletti De Palo – In: Città Sostenibili / [a cura di] C. Fiamingo, V. Bini, A. Dal Borgo. – Prima edizione. – Broni : Altravista, 2018 Dec. – ISBN 9788899688400.

Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process. Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice

Authors: Vita Žlender , Ina Šuklje Erjavec, Barbara Goličnik Marušić

This research aimed to explore information and communication technologies (ICT) types to support co-creation activities in public open spaces (POS) at different stages of the co-creation process.

We conducted state-of-the-art research on the methods, best practices, obstacles and potential of ICT tools and co-creation activities to ease the interaction between stakeholders engaged in the process.

Based on those findings, we proposed an ICT tools selection framework. Four living labs were analysed to better understand the practical side of digitally aided co-creation.

We conclude by exposing challenges and suggest ways to move forward toward genuinely digitally supported co-creation of the POS.

Vita Žlender , Ina Šuklje Erjavec & Barbara Goličnik Marušić (2020): Digitally Supported Co-creation within Public Open Space Development Process: Experiences from the C3Places Project and Potential for Future Urban Practice, Planning Practice & Research, DOI: 10.1080/02697459.2020.1829286

Mapping Digital Co-Creation for Urban Communities and Public Places

Authors: Monika Mačiulienė

Increasingly digital communication, social media and computing networks put the end-users at the center of innovation processes, thus shifting the emphasis from technologies to people. In the private sector, this shift to user-centricity has been conceptualized under such approaches as Service-Dominant Logic and Open Innovation 2.0.

Public sector conceptualizes the change through the New Public Governance and Open Government paradigms and suggest that the public value is no longer created by the governments alone but in collaboration between the public entities, private sector, civil society organizations and citizens.

While traditional approaches to public engagement and governmental transformations remain relevant, this article focuses on the growing potential of networked urban communities to solve the social problems. It expands the co-creation research field and suggests a typology discerning co-creation patterns when enhancing the public spaces with a community-wide participation with the use of creative, innovative and cooperative Information and Communication Technologies’ applications.

The sample for web-based monitoring consists of 10 digital applications linked with design and improvement of public spaces in Vilnius, Lithuania. The proposed typology framework gives an overview of the state-of-art in the interaction between people, places and technology. The research helps to discern how different technological, organizational and other social factors influence and shape the patterns of co-creative initiatives.

Mačiulienė, M. (2018). Mapping Digital Co-Creation for Urban Communities and Public Places. Systems, 6(2), 14. doi:10.3390/systems6020014

Classifying urban public spaces according to their soundscape

Authors: Kang Sun, Karlo Filipan, Francesco Aletta, Timothy Van Renterghem, Toon De Pessemier, Wout Joseph, Dick Botteldooren, Bert De Consel

Cities are composed of many types of outdoor spaces, each with their distinct soundscape. Some of these soundscapes can be extraordinary, others are often less memorable. However, most locations in a city are not visited with the purpose of experiencing the soundscape. Consequently, the soundscape will not necessarily attract attention. Existing methods based on the circumplex model of affect classify soundscapes according to the pleasure and arousal they evoke, but do not fully take into account the goals and expectations of the listener. Therefore, in earlier work, a top-level hierarchical classification method was developed, which distinguishes between spaces based on the degree to which the soundscape creates awareness of the acoustical environment, matches expectations and arouses the listener.

This paper presents the results of an immersive laboratory experiment, designed to validate this classification method. The experiment involved 40 participants and 50 audiovisual recordings drawn from the Urban Soundscapes of the World database.

It is shown that the proposed classification method results in clearly distinct classes, and that membership to these classes can be explained well by physical parameters, extracted from the acoustical environment as well as the visual scene.

Sun, K., Filipan, K., Aletta, F., Van Renterghem, T., De Pessemier, T., Joseph, W., … De Coensel, B. (2019). Classifying urban public spaces according to their soundscape. In M. Ochmann, M. Vorländer, & J. Fels (Eds.), Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress on Acoustics : integrating 4th EAA Euroregio 2019 : 9-13 September 2019 in Aachen, Germany (pp. 6100–6105). Aachen, Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Akustik.

Interactive soundscape augmentation of an urban park in a real and virtual setting

Authors: Timothy Van Renterghem, Kang Sun, Karlo Filipan, Kris Vanhecke, Toon De Pessemier, Bert De Consel, Wout Joseph, Dick Botteldooren

Inappropriate soundscapes are able to strongly deteriorate the user experience in parks. A possible remediation is adding positively perceived sounds.

The case of an urban park, fully surrounded by road traffic noise sources, was studied to explore the potential of adding natural sounds in an interactive way. A preliminary test was conducted in the lab with Virtual Reality (VR) glasses and headphones.

The audio-visual representation of the real environment was obtained by combining binaural recordings with first-order ambisonics and 360-degree video camera footage.

The users were allowed to mix in eight types of natural sounds until their personal optimized soundscape was composed. This was done in a very similar setup as in the (real) park. The loudspeaker augmenting the sound environment in the park was steered with a smartphone application.

This app ensured the user’s presence near the loudspeaker and allowed to gather more detailed assessments of the perceived sound environment through questionnaires. This combination of experiments allowed checking the validity of VR that is becoming increasingly popular in audio-visual interaction studies. In addition, the most preferred natural sounds and the way they influenced environmental noise perception were analyzed.

Van Renterghem, T., Sun, K., Filipan, K., Vanhecke, K., De Pessemier, T., De Coensel, B., … Botteldooren, D. (2019). Interactive soundscape augmentation of an urban park in a real and virtual setting. In M. Ochmann, M. Vorländer, & J. Fels (Eds.), Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress on Acoustics : integrating 4th EAA Euroregio 2019 : 9-13 September 2019 in Aachen, Germany (pp. 899–903). Aachen, Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Akustik.

Influence of Personal Factors on Sound Perception and Overall Experience in Urban Green Areas. A case study of a cycling path highly exposed to road traffic noise

Authors: Francesco Aletta, Timothy Van Renterghem, Dick Botteldooren

In contemporary urban design, green public areas play a vital role. They have great societal value, but if exposed to undue environmental noise their restorative potential might be compromised. On the other hand, research has shown that the presence of greenery can moderate noise annoyance in areas with high sound levels, while personal factors are expected to play an important role too.

A cycling path bordered by vegetation, but highly exposed to road traffic noise, was here considered as a case study. A sound perception survey was submitted to participants on site and they were subsequently sorted into groups according to their noise sensitivity, visual attention and attitude towards greenery.

The aim of this study was testing whether these three personal factors could affect their noise perception and overall experience of the place. Results showed that people highly sensitive to noise and more sceptical towards greenery’s potential as an environmental moderator reported worse soundscape quality, while visually attentive people reported better quality. These three personal factors were found to be statistically independent. This study shows that several person-related factors impact the assessment of the sound environment in green areas. Although the majority of the respondents benefit from the presence of visual green, policy-makers and planners should be aware that for a significant subset of the population, it should be accompanied by a tranquil soundscape to be fully appreciated.

Aletta, F., Van Renterghem, T., & Botteldooren, D. (2018). Influence of Personal Factors on Sound Perception and Overall Experience in Urban Green Areas. A Case Study of a Cycling Path Highly Exposed to Road Traffic Noise. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1118. doi:10.3390/ijerph15061118

Can attitude towards greenery improve road traffic noise perception? A case study of a highly-noise exposed cycling path

Authors: Francesco Aletta, Timothy Van Renterghem, Dick Botteldooren

This study was based on an on-site survey along a highly noise exposed cycling path immersed in the green, in close proximity of Antwerp Ring Road in Belgium.

The survey was held at 181 passers-by during a working week in September 2017. The survey included questions about overall cycling/walking experience, perceived loudness of road traffic noise, soundscape appreciation, perceived dominance of sound sources, and overall attitude towards greenery’s potential to reduce noise and improve air quality.

A k-means cluster analysis was performed on the scores of the attitude towards greenery (ATG) questions to create an ATG variable reflecting two profiles of users: “positive” and “sceptical” towards greenery’s potential.

The effect of ATG on overall cycling/walking experience, perceived loudness of road traffic noise, soundscape appreciation and perceived dominance of sound sources was tested through a set of independent samples t-tests. Results show statistically significant differences between the positive and the sceptical group for the dimensions of annoyance and calmness, perceived loudness of road traffic noise and perceived dominance of road traffic sounds and natural sounds.

However, no difference was observed for the two groups in terms of overall cycling/walking experience, suggesting that, for the investigated case, other factors might be playing a role.

Aletta, F., Van Renterghem, T., & Botteldooren, D. (2018). Can attitude towards greenery improve road traffic noise perception? A case study of a highly-noise exposed cycling path. In Proceedings of the 11th European Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering (pp. 2377–2382). Hersonissos, Crete, Greece.

Brief notes on user’s participation in public spaces planning and design

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

For C3Places a public space must be inclusive and responsive, allowing people to use it without restrictions and to fulfil socio-spatial needs. To achieve more inclusive and responsive spaces, users should have a voice in the process of planning and design, also known as placemaking (PPS, n. d.).

Engaging people actively calls for appropriate methodologies as inclusive design (Carmona, Heath, Tiesdell, & Oc, 2003) or co-creation, the last is at the core of C3Places research.

C3Places uses the terms inclusive and responsible place to describe a far-reaching framework of principles and best-practice on which communities can build a shared commitment to sustainability in social and urban development. For that, communities should be engaged in the making and transforming of public spaces from the very beginning.

Public space as a shared common good is the fundamental premise – public space is a resource which, if used responsibly, can help transform the way people live, work, recreate, and interact. In placemaking, stakeholders should have a clear understanding on how specific characteristics and shapes affect the experience of the space (Alves, 2005; Stevens, 2007).

Therefore, interested parties as different users’ groups, community facilitators, professionals, local authorities and municipalities, should be engaged directly, their opinions accounted for and their needs responded to by placemaking (Alves, 2005; Carmona et al., 2003; Thompson, 2002; UN-Habitat, 2015).

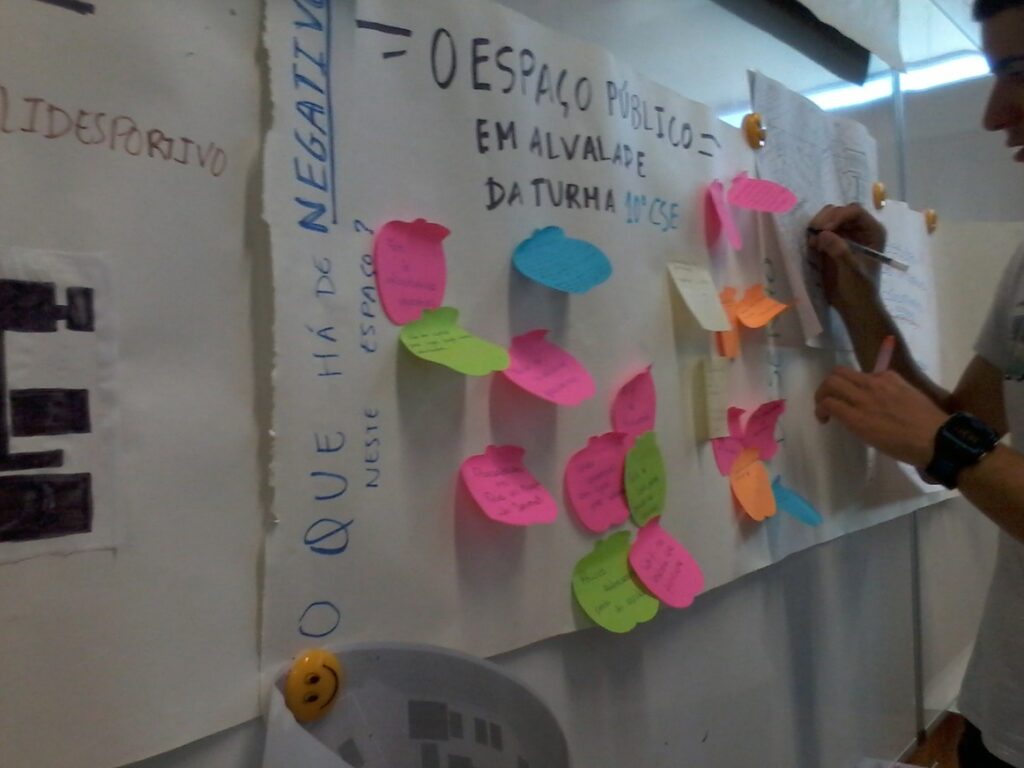

The case-study in Lisbon followed this recommendation and different stakeholders were brought together in the development and operationalisation of Living Labs (Figures 1 and 2) (Smaniotto-Costa, Almeida, Batista & Menezes, 2018).

Figure 1: Living Lab Lisbon – brainstorming exercise with participants to reflect on characteristics of and ideal public space. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2018)

Participative approaches bring challenges of different sorts: in terms of time to be invested, human resources, monitoring and structuring the process that may impose demands that are too high for planners and authorities to see the advantages; in deciding who to involve; the time offset between participation in the process and benefitting from the outcome may be too long for users to engage and, due to transitory needs of users’, too stretched to provide a response while the changes are still valid; questions may be considered too technical or complex for the comprehension of non-professionals and; participation may add a legitimacy to the process but without truly respecting the opinions and ideas of those involved (Alves, 2005; Jupp, 2007; Talen, 2000; Valentine, 2004).

Figure 2: Living Lab Lisbon – group work to draw ideas and proposals for transformation of a public open space. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2019)

However, creating collaborative environments for planning, designing and transforming public spaces is fundamental for a placemaking process more interactive and able to meet the needs of the community, and to produce public places that are more attractive, meaningful, inclusive and sustainable.

Co-creation, as an open process with no previous fixed results, is a challenge for all parts involved but it is at the same time an open door for innovative ideas and solutions. In co-creation a broader range of people come together around the same table to negotiate and reconcile their different needs and interests, solve problems, freely express their concerns and expectations and, ideally, foster a community around public spaces ensuring more sustainable use (Figure 3).

The experiences gained within C3Places in the Living labs in Ghent, Lisbon, Milan and Vilnius are described at the site MyC3Place.

Figure 3: Living Lab Lisbon – outdoor exercise for participants to observe and discover different public open spaces. Photo C3Places Lisbon (2018)

References:

- Alves, F. B. (2005). O Espaço Público Urbano. Qualidade, Avaliação e Participação Pública. Porto: Escola Superior Artística do Porto.

- Carmona, M., Heath, T., Tiesdell, S., & Oc, T. (2003). Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. Michigan: Architectural Press.

- Jupp, E. (2007). Participation, local knowledge and empowerment: Researching public space with young people. Environment and Planning A, 39(12), 2832–2844.

- PPS – Project for public spaces. (2017) The Placemaking Process.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Almeida, I., Batista, J., Menezes, M. (2018). Envolver adolescentes no pensar a cidade: reflexão sobre oficinas temáticas de urbanismo no Bairro de Alvalade, Lisboa. Engaging teenagers in placemaking: Reflections on thematic workshops in urban planning in Lisbon’s Alvalade Neighbourhood. Revista de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território (GOT), 15, 117-142, (in Portuguese).

- Stevens, Q. (2007). The Ludic City. London and New York: Routledge.

- Talen, E. (2000). The Problem with Community in Planning The Problem with Community, 15(2).

- Thompson, C. W. (2002). Urban open space in the 21st century. Landscape and Urban Planning, 60(2), 59–72.

- UN-Habitat. (2015). Adequate Open Public Space in Cities. A Human Settlements Indicator for Monitoring the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda.

- Valentine, G. (2004). Public space and the culture of childhood. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Brief notes on social value of public spaces

Authors: Joana Batista, Inês Almeida, Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Marluci Menezes

Public space is here conceptualised following UN-Habitat (2015, 15) as “all places publicly owned or of public use, accessible and enjoyable by all for free and without profit motive”. Among them are streets, squares, plazas, marketplaces, parks, green spaces, greenways, community gardens, playgrounds, waterfronts, urban forests and agricultural used land. C3Places research focus only on urban public open spaces.

Public spaces have been idealised as democratic domains, places of inclusiveness where is possible to be among friends and strangers, encounter differences and engage in planned or serendipitous interactions (Innerarity, 2006). Central to a city well-being, public spaces contribute to the quality of urban life, fostering social, cultural and economic capital (UN-Habitat, 2016). A vast body of literature focus on their social function (Figure 1), as providers of the place for peoples’ interaction with other people (Carmona, Heath, Tiesdell, & Oc, 2003; Gehl, 1987; Innerarity, 2006; Jacobs, 1961; Lefebvre, 1991; Sennett, 1977) and with their environment (Smaniotto & Menezes, 2016). Public spaces act as stage for the enactment of citizenship, to practice publicness, and as such they play a key role within the complex social infrastructure (Smaniotto Costa & Menezes, 2016). Societies’ differences and similarities are put on display in public spaces, allowing distinct groups to claim their right to appropriate particular places and manifest their sense of belonging to society (Innerarity, 2006; Mitchell, 1995). Public spaces enable symbolic identification (Carmona et al., 2003), they are the places where social and cultural identities and the individuals’ role in their community are negotiated, and this may foster the context for mutual understanding and respect, enabling the development of social bonds. Yet, historically, public space was also the site where power structures manifested themselves and dominant social and moral orders were produced, imposed and perpetuated (Sennett, 1977).

Moreover, those public spaces covered by plants and with soft surfaces (Figure 2) offer further environmental benefits as they improve the urban environmental quality (such as air purification, water storage, CO2 sequestration) and provide space for leisure and recreational activities (Smaniotto Costa, Suklje Erjavec, & Mathey, 2008).

They offer also further benefits for public mental health (Muñoz, 2009) and for decreasing in contemporary health problems as obesity and sedentarism (Godbey, 2009). Jacobs (1961) and Gehl (1987) drew attention to the importance of putting people at the centre of public space, analysing how people appropriate specific places, what are their spatial practises and needs towards creating better and more inviting public spaces.

C3Places following those premisses is analysing how specific users – teenagers or elderly – appropriate urban public open spaces and how they can be better configurated to respond to different needs. In Lisbon, observations seem to indicate that urban public spaces of transit, as streets (Figure 3), are used mainly for matters of convenience and proximity to primary spaces of daily significance as the home and the school (TBA).

References

- Carmona, M., Heath, T., Tiesdell, S., & Oc, T. (2003). Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design. Michigan: Architectural Press.

- Gehl, J. (1987). Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Godbey, G. (2009). Outdoor Recreation, Health, and Wellness: Understanding and Enhancing the Relationship. Recreation, May 2009, 1–42.

- Innerarity, D. (2006). O novo espaço público. Lisboa: Teorema.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and life of Great American Cities. New York and Toronto: Vintage Books – Random House.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Production.

- Mitchell, D. (1995). The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy. Annals of the Association of American Geographers.

- Muñoz, S.-A. (2009). Children in the Outdoors: A literature Review. Forres: Sustainable Development Research Centre.

- Sennett, R. (1977). The Fall of Public Man. London: Penguin Books.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Menezes, M. (2016). A agregação das tecnologias de informação e comunicação ao espaço público urbano. Reflexões em torno do projeto CyberParks – COST TU 1306. urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana (Brazilian Journal of Urban Management), 8 (3): 332-344. Doi: 10.1590/2175-3369.008.003.AO04.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Šuklje Erjavec, I., Kenna, T., de Lange, M., Ioannidis, K., Maksymiuk, G., de Waal, M. (Eds.) (2019): CyberParks – The Interface Between People, Places and Technology – New Approaches and Perspectives. Cham: Springer, Series: Information Systems and Applications LNCS 11380. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-13417-4.

- Smaniotto Costa, C., Suklje Erjavec, I., & Mathey, J. (2008). Green Spaces – a Key Resources for Urban Sustainability. The GreenKeys Approach for Developing Green Spaces. Urbani Izziv, 19(2 Mestne zelene površine / Urban green spaces), 199–211.

- UN-Habitat. (2015). Adequate Open Public Space in Cities. A Human Settlements Indicator for Monitoring the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda.

- UN-Habitat. (2016). New Urban Agenda: Quito Declaration on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All. In Habitat III Conference (p. 24). United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).